Plant-based ‘meat’ vs grass-fed meat

Executive summary

* A paper was published in Nature Scientific Reports in July 2021. It used an analytical profiling technique (metabolomics) to compare plant-based ‘meat’ and grass-fed meat for thousands of nutrients and outputs of the metabolic process (metabolites).

* The paper was written within the context of the increased interest in, and incidence of, plant-based ‘meat’ alternatives.

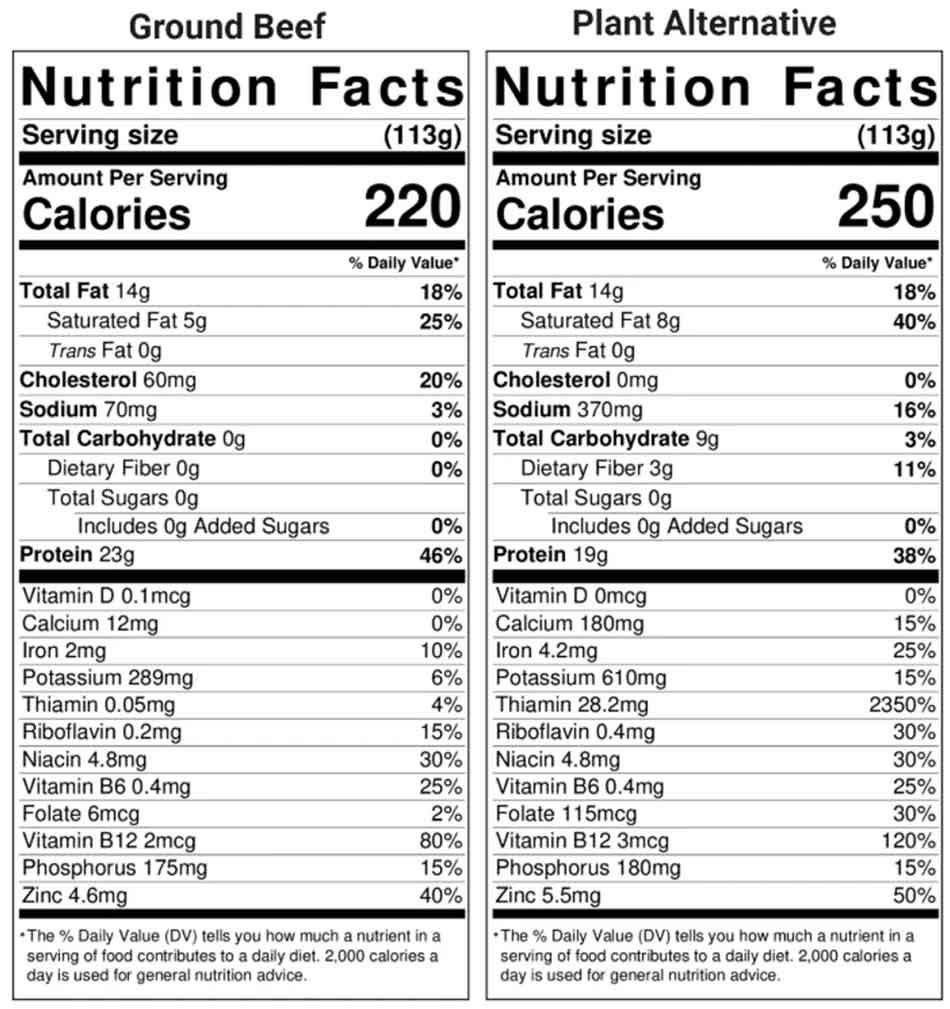

* The researchers examined numerous samples of plant-based meat vs grass-fed meat, which started from a similar serving size (113g), fat content (14g), saturated fat content (5-8g) and calories (220-250), but the differences were far greater than these starting similarities. The plant and meat burgers were strikingly different.

* There were many interesting points in the paper:

– How they make plants more ‘meat-like.’

– The nutrients commonly added to plant-based products.

– Evidence for fortified nutrients not being the same as natural nutrients.

– Plant-based products contain phytosterols and saccharides and other substances that may be undesirable.

– Plant-based burgers are processed and processed food is processed food.

– There are approximately 26,000 products and by-products of metabolism (metabolites). Fortifying a plant product with a single nutrient found in meat doesn’t start to replicate the synergistic health benefit of the real thing.

* The authors concluded that “a plant burger is not really a beef burger.” No kidding!

Introduction

Many thanks to Virginia for spotting this week’s study, which turned out to be interesting and informative. When I started writing academic papers, I was advised to ensure that the title summed up the conclusion of the paper and this one did. It was called "A metabolomics comparison of plant‑based meat and grass‑fed meat indicates large nutritional differences despite comparable Nutrition Facts panels" (Ref 1). It was published in Nature Scientific Reports on July 5th, 2021.

The paper defined Metabolomics as “an analytical profiling technique that allows researchers to measure and compare large numbers of nutrients and metabolites present in biological samples.”

A metabolite is an intermediate or end product of metabolism. There are primary and secondary metabolites. Examples of primary metabolites are ethanol, glutamic acid, aspartic acid, 5′ guanylic acid, acetic acid, lactic acid, glycerol, etc. Examples of secondary metabolites are pigments, resins, terpenes, ergot, alkaloids, antibiotics, naphthalenes, nucleosides, quinolones, peptides, growth hormones, etc (Ref 2). Don’t worry about any of these words at this stage. I’m not familiar with almost all of them and you might not be either. It doesn’t matter. We’ll be able to see what the paper did and found without knowing what terpenes, or quinolones, are, for example.

Background

This paper was written within the context that, by 2050, it is expected that we will need to feed almost 10 billion people. There is a belief that meat is bad for the planet. I do not subscribe to this belief. On the contrary, I think that grazing ruminants are the only way in which we can protect topsoil to feed the planet’s population naturally. If we remove meat and ruminants from the equation, we also destroy soil and our ability to grow food. Food would then need to be made in factories and not fields. This would be a win for big food, but a loss for human health, in my view.

Impossible Burger and Beyond Burger are two plant options being promoted as alternatives to meat burgers. The success of these products has led to other food companies (including traditional meat companies) investing in their own plant versions. "The global plant-based meat alternative sector has experienced substantial growth and is projected to increase from $11.6 billion in 2019 to $30.9 billion by 2026 with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 15%. In contrast, the meat sector is expecting a CAGR of 3.9% during this time and to reach a market value of $1,142.9 billion by 2023" (Ref 3).

The opening two sentences gave the rationale for the paper: “A new generation of plant-based meat alternatives — formulated to mimic the taste and nutritional composition of red meat — have attracted considerable consumer interest, research attention, and media coverage. This has raised questions of whether plant-based meat alternatives represent proper nutritional replacements to animal meat.”

The researchers set out to provide an in-depth comparison of the metabolite profiles of 18 samples of grass-fed ground beef and 18 samples of a popular plant-based meat alternative. The samples were chosen to be similar on their Nutrition Fact panels (see image). Both had a serving size of 113g; both had 14g of total fat. The ground beef had 5g of saturated fat; the plant alternative had 8g of saturated fat. The ground beef was 220 calories per serving and the plant alternative was 250 calories per serving. That was where the similarities ended.

The paper

I enjoyed reading the paper. It was a mix of things that I didn’t know, easily readable passages and sections that only my biochemist friend might understand. I liked the layout – which had the readable introduction, results and discussion up front and then the ‘anything but easy to understand’ materials and methods were at the end. The latter section went into minute detail about how samples were taken from the meat and plant products, what subsequently happened to the samples, what machinery was used, what tests were performed and what statistical analysis was undertaken. I cannot critique this, as it is merely reporting what was done in labs and with statistical software. However, I have no reason to think that it was anything other than robust and meticulous.

The results

The main results – repeated in the abstract and in three other places in the paper – were that:

i) a total of 171 out of 190 annotated metabolites (90%) were different between beef and the plant-based alternative; and

ii) several compounds were found either exclusively (22 metabolites) or in greater quantities in beef (51 metabolites) compared with the plant-based meat alternative.

Both findings were statistically significant.

Figure 3a in the paper was a clever diagram, which they called a heat map. It showed whether the meat or plant product was higher or lower for the top 50 metabolites that were most significantly different between the two. Picking a couple of examples, of which we will have heard, the plant product was significantly higher in vitamin C (the meat burger would have had none) and the meat burger was significantly higher in the omega-3 fatty acid DHA (the plant product would have had none). The map showed at a glance how different the meat and plant burgers were.

In the discussion section of the paper, the authors wrote “we conclude that a plant burger is not really a beef burger.” That was the best summary of the whole study. There were many other gems contained in this paper…

Interesting points

* How they make plants more ‘meat-like’.

The paper discussed individual ingredients that are used in plant burgers to try to make them more like meat burgers. For example, soy leghemoglobin imitates the “bloody” appearance and taste of heme proteins in meat. Extracts from red beets, red berries, carrots, and/or other similarly coloured vegetables are used to replicate the reddish “meat-like” appearance. Methyl cellulose is often used to give plant-based meat alternatives a “meat-like” texture, while flavouring agents are added to mimic the taste of cooked meat. Meat alternatives try to match the protein content of meat by using isolated plant proteins (e.g., soy, pea, bean, mycoprotein, as examples), although plant proteins are incomplete as an amino acid profile (Ref 4). Plant products are also sometimes fortified with vitamins and minerals found in red meat (e.g., vitamins B12, zinc, and iron) to provide an even more direct nutritional replacement.

* The concept of a plant burger is not new.

The paper reported that, in 1899, John Harvey Kellogg wrote the following in his patent application for ‘Protose’ (a plant-based meat alternative based on wheat gluten): “The objective of my invention is to furnish a vegetable substitute for meat which shall possess equal or greater nutritive value in equal or more favorable form for digestion and assimilation and which shall contain the essential nutritive elements in approximately the same proportion as beef and mutton and which substitute has a similar flavor and is as easily digestible as the most tender meat” (U.S. Patent No 670283A).

* Meat nutrients are natural; plant ones often aren’t.

The product information part of the results section of the paper summarised the similarities on the Nutrition Facts Panel. Both products had a serving size of 113g; both had 14g of total fat. In that serving size, the beef product contained 23g of protein and 0g of carbohydrate. The plant product contained 19g of protein and 9g of carbohydrate. The Nutrition Facts image also shows micronutrients. The plant burger was fortified with iron (from soy leghemoglobin), vitamin C, thiamine (B1), riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and zinc. The micronutrients within the grass-fed beef are natural to that food. Beef needs no fortification.

* Fortified nutrients are not the same as natural nutrients.

The paper explained that approximately 150 nutrients are commonly tracked in health databases, of which only 13 routinely appear on nutrition labels (fat, saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, sodium, carbohydrate, fiber, sugar, protein, vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, and iron). However, there are more than 26,000 metabolites in the human ‘foodome’ and these likely have synergistic complexity, which means that we cannot just fortify a substitute with an isolated nutrient and hope that it has the same health benefit.

The paper referenced peer-reviewed literature which showed that "consuming isolated nutrients or fortified foods often do not confer similar benefits when compared to ingesting nutrients as part of their whole-food matrix" (Ref 5). An example given was that supplementation of a low-meat diet with zinc and other minerals found in meat did not result in a similar in vivo zinc status when equivalent amounts of these minerals were provided as would occur naturally in meat (Ref 6). (In vivo means in a living organism).

“Similar findings have been made for other nutrients, such as copper, calcium and vitamins A, C, and D, which are associated with disease protection when obtained from food, but often not when obtained from fortified or supplemental sources” (Ref 7).

The uptake of minerals is also not the same from fortified plant foods as from meat. Iron in animal foods is in the heme form, which is the most bio-available (absorbable). Uptake of zinc from plant foods is also reduced due to the presences of phytates, lectins and other ‘anti-nutrients’.

* Plant alternatives contain some undesirable substances.

The metabolites called phytosterols were found exclusively in the plant-based product when compared to beef. This fact was presented as a possible health benefit in the paper. However, I have researched phytosterols because of their impact on cholesterol lowering and I have found associations with concerning heart and cancer outcomes with phytosterol consumption (Ref 8). Saccharides, glycerides, sugar alcohols and sugar acids were also found mainly or exclusively in the plant products.

* Real vs processed food.

Processed food is processed food, even if it is intended to be a healthy alternative to a real food. The researchers referenced a paper by Hu and colleagues (the Harvard team), which expressed reservations about the ultra-processed nature of plant-based meat alternatives (Ref 9). This was quite amusing, as the Harvard school of public health generally is pro plant and anti-meat. Further citations were given in the paper to support the conclusion that “not all plant-based diets are necessarily healthy, and diets rich in ultra-processed foods are associated with increased chronic metabolic disease risk, irrespective of whether they are plant-based or mixed (omnivorous)” (Ref 10).

For these many reasons, the authors concluded that “a plant burger is not really a beef burger.” They added that the plant and meat burgers “should not be viewed as nutritionally interchangeable.” I would add that, if there is anything missing in meat (and if you consume all parts of the animal there shouldn’t be) you can get it elsewhere. If there is something missing in a plant-based diet, and you consume only plants, you can’t get that elsewhere. Yes, supplements are available, but we cannot rely on these to provide the body with what it needs in the same way. Certainly not when there are approximately 26,000 products and by-products of metabolism.

My single biggest takeaway was related to that 26,000 figure. We need to view eating as magnitudes more than macronutrients and micronutrients. When we eat meat, yes, we consume macronutrients and micronutrients, but we also set off an orchestra of metabolic processes and products and by-products. These will work together to provide health benefits. If we think we can add zinc and iron to some soy and beetroot and think it’s ‘’like eating meat’, we need to think again.

The Independent newspaper in the UK covered this article with the headline “Plant-based meat not nutritionally equivalent to real meat, finds study” (Ref 11). That was a good summary, but the paper contained so much more of real interest. Nice find Virginia!

References

Ref 1: Van Vliet et al. A metabolomics comparison of plant-based meat and grass-fed meat indicates large nutritional differences despite comparable Nutrition Facts panels. Nature Scientific Reports. July 2021.

Ref 2: https://www.biologyonline.com/dictionary/metabolite

Ref 3: STATISTA. Meat substitutes market in the U.S. https:// www. statista.com/ (2020).

Ref 4: https://www.zoeharcombe.com/2020/07/animal-vs-plant-protein/

Ref 5: Jacobs & Tapsell. Food, not nutrients, is the fundamental unit in nutrition. Nutr. Rev. 2007.

Ref 6: Hunt et al. High- versus low-meat diets: Effects on zinc absorption, iron status, and calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, nitrogen, phosphorus, and zinc balance in postmenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995.

Ref 7: Xiao et al. Dietary and supplemental calcium intake and cardiovascular disease mortality: The National Institutes of Health–AARP Diet and Health Study. JAMA Intern. 2013.

Chen et al. Association among dietary supplement use, nutrient intake, and mortality among U.S. adults: A cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019.

Ref 8: Harcombe Z, Baker J. Plant Sterols lower cholesterol, but increase risk for Coronary Heart Disease. Online J Biol Sci. 2014.

Ref 9: Hu et al. Can plant-based meat alternatives be part of a healthy and sustainable diet?. JAMA. 2019.

Ref 10: Satija et al. Healthful and unhealthful plant-based diets and the risk of coronary heart disease in U.S. adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017.

Julia et al. Contribution of ultra-processed foods in the diet of adults from the French NutriNet-Santé study. Public Health Nutr. 2018.

Ref 11: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/plant-based-faux-meat-nutrition-b1879454.html

Just a comment on the idea that by 2050, “it is expected that we will need to feed almost 10 billion people.”

This is an argument I did not have a good response for, until recently. Surprisingly, the Guardian had this sensible (ie not plant-biased) article recently; an interview with Mark Bittman, who pointed out that:

“No one’s asking us to feed them. In many cases, people are just asking us to leave them alone. So that, in a way is a PR ploy for big ag: “We need to increase yield forever, so that we can feed the world.” But the world does not want us to feed them. The world wants us to stop stealing their land and stop poisoning them and so on. At least, that’s my perception of the world.”

https://bit.ly/3icMvel

Let’s remind the do-gooders that UPF junk food = cheap + convenience = corporate profits = addictive = society pays the hidden costs.

And let’s get out of the way of the small farmers and their choice of livestock and plants.

The world will be better off without industrial monocultures of soy, wheat, corn etc.

Ok, problem solved… We can chuck the fake meat into the compost pile for the worms, and get back to real food.

Wishing it were that simple.