Transmission of Covid-19 post vaccination

Executive Summary

* A paper published in the BMJ in October 2020 reported that none of the Covid-19 vaccine trials were designed to test severity of outcome (hospitalisation, intensive care (ICU) or death) or transmission of the virus.

* A study has been undertaken in Scotland, to investigate a current unknown – whether vaccination can reduce transmission of Covid-19. The paper on the study has been published in pre-print, while undergoing peer review.

* The study examined approximately 150,000 healthcare workers and their approximately 200,000 household members for a period of 86 days following the start of the vaccination programme in Scotland on December 8th, 2020.

* During that period, approximately 80% of the healthcare workers got at least one dose of either the Pfizer or AstraZeneca vaccine. The study reviewed the number of cases (positive PCR test) in healthcare workers while unvaccinated and then ≥ 14 days post vaccination. It matched this to cases among household members during the period when the healthcare worker family member was unvaccinated and then vaccinated.

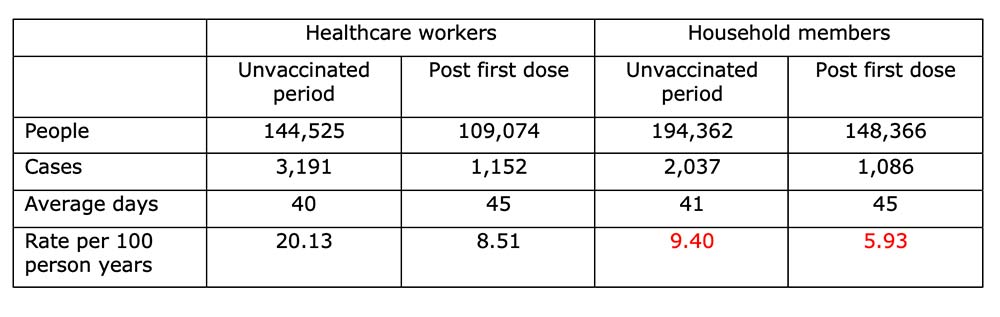

* The study reported that the positive test rate per 100 person years was 9.40 for household members during the period when the healthcare workers in the household were unvaccinated and 5.93 for household members during the period when the healthcare workers in the household were ≥ 14 days post vaccination. The conclusion was thus that “Vaccinating healthcare workers for SARS-CoV-2 reduces documented cases and hospitalisation in both those individuals vaccinated and members of their households.” (The claims made for hospitalisations were not statistically significant and should not have been made).

* The cases claim came from a particular table, which reported cases in healthcare workers and household members in the unvaccinated and vaccinated periods. The table provided an alternative conclusion. For every 100 healthcare worker cases in the unvaccinated period there were 64 household cases and for every 100 healthcare worker cases in the vaccinated period there were 94 household cases. We could conclude, therefore, that transmission was higher from healthcare workers to household members post vaccination.

* Even if the 9.40 vs. 5.93 case comparison is valid, there are many other factors that could have impacted these numbers that were not mentioned, let alone adjusted for: i) infections in Scotland generally were much higher in the unvaccinated relative to vaccinated period; ii) lockdown policy was much tighter in the vaccinated relative to unvaccinated period; iii) people were excluded from further analysis as soon as they tested positive for Covid-19, so there were fewer people in the vaccinated period to be able to test positive; and iv) people would be less likely to think they had Covid-19 post vaccination and thus less likely to test for it.

* There were a number of other interesting findings that were not highlighted in the paper:

– Healthcare workers being vaccinated had no significant impact on hospitalisation in household members.

– 27% of the positive tests among healthcare workers occurred after being vaccinated and 35% of household cases occurred after healthcare workers had been vaccinated.

– There was no significant difference in the likelihood of household members over the age of 65 testing positive after healthcare workers had been vaccinated. There was, therefore, no evidence that healthcare worker vaccination helped the most vulnerable (elderly) in the household.

* This study of healthcare workers and their households in Scotland, during varying lockdown restrictions, lacks generalisability beyond these circumstances.

* This study fails to provide convincing evidence that living with a vaccinated person makes the household member less likely to test positive for Covid-19 and it provides no evidence for serious outcomes (hospitalisation being the lowest rung of that ladder) being less likely.

Introduction

In December I reviewed two papers published that month (Ref 1). One was in the New England Journal of Medicine by Polack et al. It was called “Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine” (Ref 2). The other was the Voysey et al paper in The Lancet called “Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK” (Ref 3). The first presented the initial safety and efficacy findings for the Pfizer Covid-19 vaccine; the second presented the same for the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine.

An important BMJ article was referenced in that post (Ref 4). It was written by Dr Peter Doshi and it summarised some aspects of the vaccine trials of which I had not been aware, and I suspect many others had not been aware either:

“None of the trials currently under way are designed to detect a reduction in any serious outcome such as hospital admissions, use of intensive care, or deaths. Nor are the vaccines being studied to determine whether they can interrupt transmission of the virus.”

Table 1 in Doshi’s paper summarised characteristics of ongoing Phase 3 Covid-19 vaccine trials for Moderna, Pfizer, AstraZeneca (US), AstraZeneca (UK), Janssen, Sinopharm, and Sinovac. All the trials excluded children, adolescents, immunocompromised patients, pregnant or breastfeeding women. None were designed to evaluate reduction in severe cases (hospitalisation, intensive care (ICU), or death) and none were designed to evaluate interruption of transmission (person to person spread.) This does not seem to be widely known.

The trials were set up to measure cases, defined as a positive PCR test with at least one symptom of Covid-19. Cases were the primary outcome reported in the results, which led to the medications being approved for emergency use, while trials are ongoing. (The Pfizer trial is not due for completion until April 6th, 2023 (Ref 5) and the Oxford/AstraZeneca trial is not due for completion until February 14th, 2023 (Ref 6).)

Ideally the vaccine trials would have been designed to test the important issues – serious outcomes and transmission. We want to know if injections can prevent hospitalisation, ICU and/or death and transmission. Given that the trials didn’t test for these, we will need to rely on retrospective population studies, which provide a lower level of evidence.

A paper has been published as a preprint, which means that it has not yet been peer reviewed (Ref 7). The paper contains a caution: “NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice.”

The paper is called “Effect of vaccination on transmission of COVID-19: an observational study in healthcare workers and their households.” As the issue of transmission following vaccination is so important, I thought it would be worth reviewing this paper while it is going through peer-review.

As I was deep into the analysis for this pre-print, a peer-reviewed paper on the same topic was published based on England data (Ref 8). Both papers reviewed healthcare workers and members of their household, but the approaches were different, (and the period examined was longer for the Scotland study) so I proceeded with the Scotland paper.

The Scotland (transmission) paper

This preprint paper was undertaken on data from Scotland. The starting study population included healthcare workers employed as of March 1st, 2020 (the first positive reported case of Covid-19 in Scotland) and still employed by the NHS on November 1st, 2020. Any of these healthcare workers with a positive Covid-19 PCR test before December 8th, 2020 (the date when the vaccination programme was initiated) were excluded from the analysis.

This produced the first interesting finding – the number of people excluded from the study because they had had a positive test between March 1st, 2020 and December 8th, 2020. Originally 152,299 healthcare workers were available to be included. Only 5% of these needed to be excluded from the study because they had tested positive for Covid-19 during the nine and a bit months before December 8th, 2020 (Ref 9). That struck me as a low infection rate for NHS staff working through a pandemic.

Excluding these people left 144,525 healthcare workers (average age 44) and 194,362 household members (average age 31) who lived with them. The study examined the vaccination status of the healthcare workers to see if this had an impact on the people in their household.

The period examined was between 8th December 2020 and 3rd March 2021 (vaccination started in Scotland on December 8th). The primary endpoint of interest was a positive test for Covid-19 ≥ 14 days following the first dose of either the Pfizer (BNT162b2) mRNA vaccine or the Oxford/AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) vaccine.

The paper reported that, out of the 144,525 healthcare workers 78.3% (113,253) received at least one dose of a vaccine; 25∙1% (36,227) received a second dose. Table 1 reported that 114,257 healthcare workers had been vaccinated (adding up Dec/Jan/Feb vaccinations) and Table 2 reported 109,074 healthcare workers as “post first dose” (this should reflect those excluded for having tested positive, but this doesn’t add up either). This is in pre-print, so I hope the numerical discrepancies get sorted. I have been in correspondence with the senior author and they plan to check these and resolve the differences.

There were 3,123 and 4,343 documented Covid-19 cases and 175 and 177 Covid-19 hospitalisations in household members of healthcare workers and healthcare workers, respectively. The paper summarised the results as:

“Household members of vaccinated healthcare workers had a lower risk of COVID-19 case compared to household members of unvaccinated healthcare worker (rate per 100 person-years 9∙40 versus 5∙93; HR 0∙70, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0∙63 to 0∙78). The effect size for COVID-19 hospitalisation was similar, with the confidence interval crossing the null (HR 0∙77 [95% CI 0∙53 to 1∙10]).”

We’ll look at where those results came from shortly. The second part of that statement is disingenuous. If the confidence interval crosses the null (i.e., includes 1.0), the finding is not significant and should not be implied as such. The key findings then become; vaccination made a significant difference to transmission of cases but no significant difference to hospitalisation. (I will ignore hospitalisation for the rest of this note, as there were no significant differences). Let’s explore further.

The results

The process was difficult to follow at times and so I put it into familiar context. I know a family where the mother of the household is a healthcare worker (Jane) and the other household members are Rob (husband) and Tom (son). This study was trying to examine the impact of Jane being vaccinated on Rob and Tom. If Rob (and/or Tom – less likely) was also vaccinated, “person-time was censored on the day of their vaccination.” (i.e., they stopped being included on the day they were vaccinated.) Correspondence with the authors revealed that “only about 10% of household members were vaccinated” during the period being examined.

We started on December 8th, 2020 with 144,525 ‘Janes’ and 194,362 ‘Robs’ and ‘Toms’. Between that date and March 3rd, 2021 (which is a period of 86 days), Table 1 told us that 79% of Janes got at least one vaccine. The number of household members must have been evenly distributed because Table 1 also told us that 79% of Robs and Toms counted as living with a vaccinated Jane during that period. There were 21% of Janes unvaccinated during the period and 21% of Robs and Toms who remained living with an unvaccinated Jane during that period.

I’ve extracted the following numbers from Table 2, as the best presentation of that period. Author correspondence confirmed that the 0–13-day period from vaccination until considered post first dose was not included in Table 2 and thus not included in this table below (Note 10).

I also clarified with the authors that the numbers below present the events among household members during the healthcare workers’ unvaccinated and vaccinated period – not the household members’ own unvaccinated and vaccinated period. To spell it out I asked, “Is 148,366 the number of household people who could get infected post the first healthcare worker vaccine and is 1,086 the number of cases among that group post the healthcare worker first vaccine?” The answer was “That is correct.”

The above extracted numbers (from Table 2) show where the claimed 9.40 vs. 5.93 came from (numbers in red). Before we look at these, there are a couple of important findings from this table, which were not highlighted in the paper:

i) We started off with 144,525 unvaccinated Janes. On average, the Janes were unvaccinated for 40 days and then post their first dose for 45 days. Cases were a positive test for Covid-19, so 3,191 Janes had a positive test while unvaccinated and 1,152 Janes had a positive test while vaccinated. That’s another interesting finding – 27% of cases occurring in healthcare workers happened ≥ 14 days after vaccination (Note 11).

ii) Similarly, in Robs and Toms, 2,037 cases occurred while Janes were unvaccinated. And then 1,086 cases occurred after Janes had been vaccinated. So, 35% of household cases occurred after Janes had been vaccinated.

Back to the numbers in red. Reading down the above table, we have people, then cases and then average days in the period, so we can calculate average person days (not shown) and then the rate per 100 person years. The table reported that the rate per 100 person years was 9.40 for household members during the period when Janes were unvaccinated and 5.93 for household members during the period when Janes were ≥ 14 days post vaccination.

The paper thus concluded: “Vaccinating healthcare workers for SARS-CoV-2 reduces documented cases and hospitalisation in both those individuals vaccinated and members of their households.” There’s the disingenuous hospitalisation claim again. But is it right to conclude that vaccinating healthcare workers reduced cases in healthcare workers and/or their household members? Could anything else explain the reduced case rates?

Confounders not adjusted for

Yes, in short. There were a number of key confounders that were not mentioned, let alone adjusted for:

1) Infection rates.

Vaccination started on December 8th, 2020 and the period reviewed ended on March 3rd, 2021. There were 40-41 days on average in the unvaccinated period and 45 on average in the vaccinated period. On average, the unvaccinated period ran until approximately January 16th. Using very detailed and helpful official Scottish government data, I calculated that average cases per day were 1,517 in the unvaccinated period and 942 cases per day in the vaccinated period (Ref 12). Household members may have experienced fewer positive tests in the vaccinated period because everyone in Scotland was experiencing fewer positive tests. (We need to take care here too, because cases are a function of tests, so there are confounders on top of confounders).

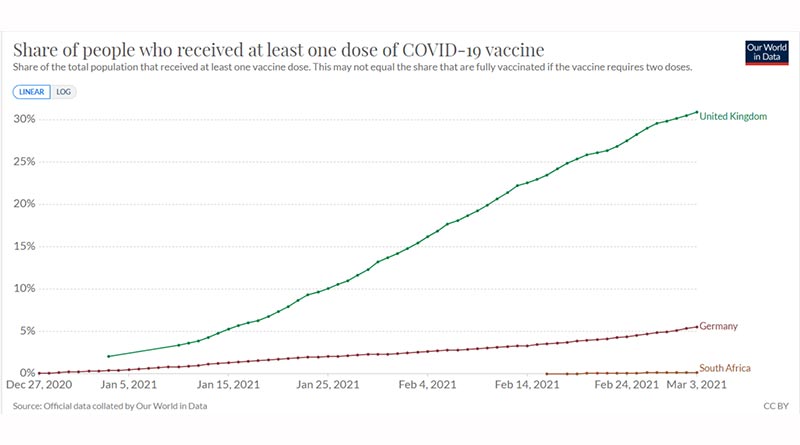

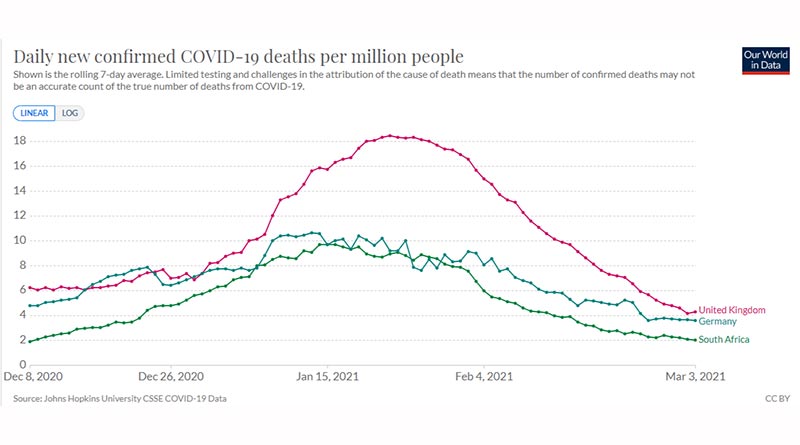

There is an argument that cases declined because of the general Scotland vaccination programme and then we’re into a circular argument of – did vaccination reduce transmission in the house or outside the house, but the idea that vaccination reduced transmission anywhere can be challenged with wider data. As of March 3rd, 2021, 30.9% of the UK had been vaccinated compared with 5.5% in Germany and 0.14% in South Africa (Ref 13). Until March 3rd, cases and deaths in both those countries followed a similar (and lower) trajectory than the UK (Ref 14). One black swan and the hypothesis is over – there’s two without looking any further. (Graphs at the end of this note).

2) Lockdown rules.

These were different in Scotland during the 86-day period (Ref 15). At and following December 8th, Scotland was in three levels – most places in level 3 – some in levels 1 & 2. On December 20th, travel between Scotland and the rest of the UK was prohibited. On December 26th, all of Scotland moved into level 4. On January 4th, 2021, a complete lockdown was imposed. On January 15th, all travel corridors were suspended. On February 15th, hotel quarantine was introduced following any type of travel. On March 3rd, furlough was extended. Hence lockdowns were tighter in the vaccinated period than the unvaccinated period. Household members may have experienced fewer positive tests in the vaccinated period because they couldn’t meet anyone outside the household.

UK Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, thinks this. On April 13th he said, “Of course the vaccination programme has helped, but the bulk of the work in reducing the disease has been done by the lockdown” (Ref 16). In case it is thought that this has made the case for lockdown, it is important to remember that, from the outset (March 2020), SAGE (the UK Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies) reported that “measures seeking to completely suppress spread of Covid-19 will cause a second peak” i.e., lockdowns have a temporary effect (Ref 17). (They flatten the curve – the don’t change the area under the curve).

3) You can only get it once.

Having had 5,228 positive tests in the unvaccinated period (when cases were higher and restrictions were fewer), there were fewer people to test positive in the vaccinated period.

4) Less likely to test.

Once people had been vaccinated, they would be less likely to think that they had Covid-19 and thus less likely to test for Covid-19. That would apply to the household members too.

The bigger issue

The main claim – 9.40 vs. 5.93 cases per 100 person years – came from reading down the table. The confounders above show that there were a number of reasons that could explain the differences in these two numbers, other than the vaccination status of the healthcare worker in that household. Reading across the table gives a different conclusion…

In the unvaccinated period there were 3,191 Jane cases and 2,037 Rob and Tom cases. In the vaccinated period there were 1,152 Jane cases and 1,086 Rob and Tom cases. This means that, for every 100 Jane cases in the unvaccinated period there were 64 Rob & Tom cases and for every 100 Jane cases in the vaccinated period there were 94 Rob & Tom cases. We could conclude, therefore, that transmission was higher from healthcare workers to household members post vaccination (Note 18).

A couple of other points

Figure 1 in the paper reported risk ratios for different subgroups of people. The different age groups were interesting. Figure 1 reported that there was no significant difference in the likelihood of household members over the age of 65 testing positive after healthcare workers had been vaccinated. There was, therefore, no evidence that healthcare worker vaccination helped the people in the household most in need of help.

There was no comparison of transmission in households where the healthcare worker remained unvaccinated during the 86-day period. It would have been useful to compare transmission in unvaccinated with vaccinated people – not just unvaccinated and vaccinated periods in the same person.

This study only applies to Scottish healthcare workers and their households and thus may lack generalisability beyond this. More importantly, the study was undertaken during periods of non-pharmaceutical interventions (lockdown measures) and thus cannot be assumed to apply to periods of normality (if that returns.)

This study fails to provide convincing evidence that living with a vaccinated person makes the household member less likely to test positive for Covid-19 and it provides no evidence for serious outcomes (hospitalisation being the lowest rung of that ladder) being less likely.

Vaccines, cases and deaths for the UK, Germany & South Africa between December 8th (27th for vaccines) 2020 and March 3rd, 2021.

References

Ref 1: https://www.zoeharcombe.com/2020/12/chadox1-ncov-19-the-lancet-papers

Ref 2: Polack et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. NEMJ. December 2020. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2034577

Ref 3: Voysey et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. The Lancet. December 2020.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)32661-1/ fulltext

Ref 4: Peter Doshi. Will covid-19 vaccines save lives? Current trials aren’t designed to tell us. BMJ October 2020. https://www.bmj.com/content/371/bmj.m4037

Ref 5: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04368728

Ref 6: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04516746

Ref 7: Shah et al. Effect of vaccination on transmission of COVID-19: an observational study in healthcare workers and their households. Pre-Print. March 21st, 2021. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.11.21253275v1

Ref 8: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/ one-dose-of-covid-19-vaccine-can-cut-household-transmission-by-up-to-half

Ref 9: Supplementary material (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.11.21253275v1. supplementary-material)

Note 10: I also asked the authors about this, as I couldn’t see how the 0–14-day period hd been accounted for. In a period of 86 days, healthcare workers were unvaccinated on average for 40 days and vaccinated on average for 45 days, so where did the 14-day period go?! The authorsa replied that “days 0-13 post first dose were not included in this table.” But I don’t see how.

Note 11: Table 2 reported that only 4% of the vaccines administered to the healthcare workers were Oxford/AstraZeneca; 96% were Pfizer. Pfizer’s efficacy rate is claimed to be 95%.

Ref 12: https://data.gov.scot/coronavirus-covid-19/detail.html#cases

Ref 13: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations

Ref 14: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases

https://ourworldindata.org/covid-deaths

Ref 15: https://www.scotsman.com/health/coronavirus/ when-did-lockdown-start-in-scotland-key-dates-and-milestones-as-country-marks-anniversary-of-covid-restrictions-3175303

Ref 16: https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/lockdown-covid-19-cases-pandemic-boris-johnson-b929418.html

Ref 17: Meeting 15 March 13th, 2020. Point 24.

( https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/ attachment_data/file/888783/S0383_Fifteenth_SAGE_meeting_on_Wuhan_

Coronavirus__Covid-19__.pdf )

Note 18: This holds if it is argued that cases as a proportion of people should be taken. In the unvaccinated period, 2.2% of healthcare workers and 1% of household members tested positive. In the vaccinated period these numbers were 1.1% and 0.7%. Again, the ratio was greater in the vaccinated period.

Great article, thank you, now if only someone could re-do this properly, paying attention to all your confounders…..

I regularly look at ourworldindata and have done the exact UK vs South Africa comparision you have done. Today it is even more illustrative.

Finally the English study you have linked to via your reference 8, (click on the “This New Research” link) starts off with the usual incorrect blather to comply with the govt narrative that lockdowns prevent infections, even going so far as to give the incorrect date for the last lockdown, late December when it was actually Jan 4th, presumably to try to prove that infections began to fall after the lockdown. So if even the introduction contains an agenda one wonders what magic they could work with statitics.

Again ourworldindata “tests” tab is very useful here, in the “Share of Tests that are +ve” graph it is clearly shown that UK +ve PCR peaked BEFORE the lockdown even started, not even accounting for the 5 day incubation period.

Hi Ben

Many thanks for your kind words.

The English paper is also just about transmission from healthcare workers to their families. This was the same with social distancing ‘evidence’ (https://www.zoeharcombe.com/2020/06/social-distancing-the-evidence/) It was just about people in the same household.

I see TV presenters talking nonsense about transmission – the study to see if you can impact me has not been done!

Did you get the paper and supplemental file OK? If not I can email them to you.

Best wishes – Zoe

Yes, via your ref 7. But I’m not a pro statistician, so I didn’t make much of it! I had enough common snese to follow your point via your condensed table, that’s about all I can manage.

But common sense shows that the critical figures are things like all cause deaths, over many years, not just 5 years.

Other factors that can demolish any pro lockdown argument:

PCR positive is not an illness

PCR positive on a death certificate is not a cause of death, at least not since the panicdemic

MSM run a panic season every winter about hospitals on the verge of collapse

Most nurses and doctors, whenever you ask them, say that things are worse than ever, not just in 2020-21.

Hospitals are always at least slightly understaffed

With regard to the peak mortality in April May 2020, as a hospital nurse I have seen group transfers on a smaller scale and know how fatal they can be, 1 in 6 to 1 in 3, and how actions that cause risk to patients can be carried out without question if people are scared into complying. You don’t have to be a junior staff to be scared to question orders.

Hi Ben

Many thanks for sharing this. We are in very troubling times. Today we have zero deaths and yet all the news headlines are of a third wave. We need to stop the fear mongering, stop the narrative and get back to living :-(

The table wasn’t much bigger than the columns I extracted. Stuff on hospitalisations, which weren’t statistically significant, so I ignored them. We still don’t have (or I am not aware of) a study that examines transmission between ordinary members of the public.

Then we have models predicting that the next wave will be mainly made up of people double jabbed – how does that happen!? (https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/vaccine-third-wave-coronavirus-modelling-20328025) “The paper suggests that the resurgence in both hospitalisations and deaths will dominated by those who have received two doses of the vaccine, comprising around 60% and 70% of the wave respectively. Worryingly this is working on the assumption that the vaccine protection will not wane or a variant emerging that escapes vaccines.”

Strange times indeed!

Best wishes – Zoe

Hi Zoe

Thank you for this website, it is one of the clearest I have been able to find. I wish I could find the article I personally found the most helpful as I really could do with being able to re-read it. What happened to your explanation of immunity?

Hi Jane

Many thanks for your kind words.

I’m not sure which one you mean. Was it this by any chance? I can’t think of anything I’ve written specifically about immunity: https://www.zoeharcombe.com/2020/12/chadox1-ncov-19-the-lancet-papers/

Best wishes – Zoe

Dr Harcombe,

Thanks for the review. I checked the references you supplied and some have been disappeared – Refs 8, 9, and 17. HMG seems to be the worst culprit.

Re your comment about a confidence interval including 1, there is also no statistically significant difference between two confidence intervals if they overlap each other.

There seems to be an assumption that healthcare workers transmit to relatives. It could also be the other way round, with subsequent enhanced healthcare spread through the nature of the working conditions. The healthcare and household infections could also be unrelated.

Another factor is the winding down of the Ct threshold from 40 to 28, now below the critical 30-35 junk threshold. That in itself will dramatically reduce test positives.

Sequence of events is a factor beyond unvaccinated / later vaccination.

Hi Ken

Many thanks for these comments.

All the links were working as of publication midday Monday! (50 hours ago).

Ref 8 is intermittently working for me https://www.gov.uk/government/news/one-dose-of-covid-19-vaccine-can-cut-household-transmission-by-up-to-half

Ref 9 you should be able to get from the RHS of the main paper page here: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.11.21253275v1

Although I suspect these pre-print pages will disappear once the paper is published.

Ref 17 PDF can be found here https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sage-minutes-coronavirus-covid-19-response-13-march-2020

I thought attaching the PDF would be easier – but clearly not safer!

Many thanks for all the other comments too – much appreciated.

Best wishes – Zoe

Hi Zoe, thanks for all that you are doing. After listening to Nick Hudson’s presentation, should more be done to differentiate between a ‘case’, an ‘infection’ and a ‘positive test result’? All three terms are being merged into just a ‘case’ so that the general public are scared by the conflation of a positive PCR test with someone in ICU.

Hi Ray

Many thanks for your kind words.

I loved Nick’s presentation and he’s right. I make sure that I use the definition of case in each paper and it’s usually either a positive test (which can be unreliable and is more unreliable if the general population case rate is low) or a positive test with at least 1 symptom. Someone being ill or very ill (hospital/ICU) is a whole different issue.

I also have days when I ponder over the SARS Co-V 2 vs Covid-19. SARS Co-V 1 was just called that. You either had it or you didn’t. (And it was largely left alone and died out in little more than a year). The virus we talk about is SARS Co-V 2, but the disease we talk about is Covid-19 – why? I wonder how much the confusion is deliberate some days!

Best wishes – Zoe

Lost and confused. how will the changing pcr thresholds effect all this?

Hi Peter

They will reduce the number of cases and hopefully make the number of cases more accurate. Prof Tim Spector estimated from his Zoe app a couple of days ago that symptomatic Covid-19 in the UK is in about 1 in 40,000 people! The sooner we stop this whole over-reaction, the better!

Best wishes – Zoe

Thanks again, Zoe, for your deep dive on this subject. Did you happen to see this, from CDC (in coming weeks, they will cease counting all cases for “vaccine breakthrough” (interesting phrase) and limit their cataloging to only serious hospitalizations and death.

https://i.imgur.com/SCT2xjk_d.webp?maxwidth=640&shape=thumb&fidelity=medium

Hi there

I hadn’t heard of this term, so thank you! But it’s important to document. One of the biggest dangers in this would be people thinking they are protected and then not being so. I would rather my elderly loved ones knew the scores on the doors, as they say!

Best wishes – Zoe

The effect of counting only the most serious cases of post-vaccination [covid] hospitalizations/deaths will make the vaccines appear safer.

Here’s their page on the subject:

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/health-departments/breakthrough-cases.html

I was under the impression that none of the vaccines had SARS-CoV-2 virus included, simply fragments with mundane or innovative delivery means.

Claiming vaccine breakthrough from a protein sequence in the same way that it ‘was’ possible with an attenuated virus vaccine sounds fishy to me.

A lot of the timing and marketing is clever and complex. I think there is simply so much money involved here that the gloves are off and any technique that may assist with (future) sales is used.

There was a chap Alex Vasquez who made some noise about the Vaccine trial in Scotland way back when and I believe that the benefits ascribed to vaccines will in truth be VERY HARD to prove given the massive amount of media attention that Vitamin-D has had this time round.

https://www.bmj.com/content/365/bmj.l1375/rr-4

vdmeta.com