How to assess evidence in nutrition

Executive summary

Please login to view this content

Introduction

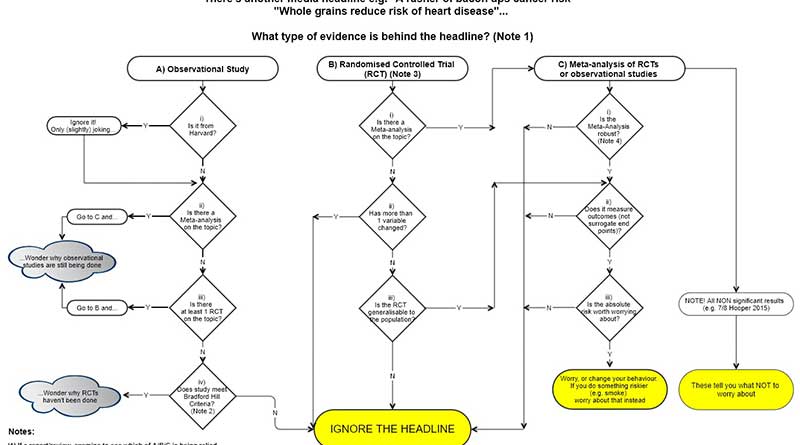

I’ve just got back from the west coast of the US where I spoke at two CrossFit events. The first event was for doctors and the second was for the top CrossFit trainers in the world. For the doctors’ talk, I presented a flow chart that I have been working on for some time. It was inspired by a tweet from Professor Tim Noakes a while back. Tim tweeted “If assoc studies found something real, RCTs would confirm. Have not. Why doesn't @HarvardHealth admit?” Nutritional evidence nailed in 15 words.

Evidence is supposed to work in the following way – an observation is made and then this is tested in a trial. e.g. a population study might observe an association between people with a high junk food diet and high blood pressure. To test whether this association is causal, researchers should conduct a randomised controlled trial (RCT) where people are randomly assigned to either their normal diet (change nothing) or to adopt a specified high junk food diet. The trial would work out beforehand how many people would be needed and over what time period to establish a significant difference between the junk diet and the normal diet – if there is one.

If one RCT showed that, for example, eating a junk food diet for four weeks significantly raised blood pressure this would be an interesting, but isolated, finding. Ideally, this would lead to further research so that we would know how much junk food, and over what time period, would be needed to raise blood pressure and by what amount. Over time we should end up with a number of randomised controlled trials and then these could be pooled together in the technique called meta-analysis to provide an overall idea of the impact that junk food has on blood pressure. Blood pressure is still only a marker. Longer trials would be needed to see if a junk food diet made a significant difference to things that matter i.e. death and disease.

Tim’s tweet was in response to the production line of epidemiological (observational) papers that are incessantly published by Harvard. I have covered many of these papers during the 10 years I’ve been doing this Monday note. They usually say meat, eggs and/or dairy are bad and fruit, vegetables and whole grains are good. Tim was therefore saying – if your observational claims about animal foods being bad and plant foods being good were genuine findings, there would be randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to prove that the association is causal. But there aren’t. So why don’t you admit that?

It made me think – what evidence in nutrition is worth taking note of? What do we really know? The earliest dietary RCTs of value date back to the 1960s. The Israel Registry Study – an epidemiological study – dates back to 1968. The most renowned observational studies started in later decades. The US Nurses Health Study started in 1976. The male Health Professionals Follow-up Study started in 1986. There are remarkably few original RCTs and observational studies – especially given the number of papers on nutrition that are published.

The rest of this article is available to site subscribers, who get access to all articles plus a weekly newsletter.

To continue reading, please login below or sign up for a subscription. Thank you.