Fats & Bladder cancer

Executive Summary

* This week’s note looks at a paper which examined the association between dietary fat intake (all fats, saturated fat, monounsaturated fat, polyunsaturated fat and dietary cholesterol) and incidence of bladder cancer.

* The main risk factors for bladder cancer were age (older people had more cases), sex (men had more cases) and being a current or former smoker (smokers/ever smoked had more cases).

* The paper was reported in the media as "Saturated and animal fats ‘could increase bladder cancer risk in men." The study found nothing related to saturated fats. The claim for animal fats was based on a 0.06g difference in intake, which is barely measurable.

* The differences in intakes of all fats between the cases and non-cases was tiny.

* No associations were found for incidence of bladder cancer and total lipids, total fatty acids, saturated fatty acids and/or polyunsaturated fatty acids.

* The paper tried to argue that, once we adjusted for what really mattered (age, sex and smoking) there was one finding for women and another for men.

* One association was found for monounsaturated fat being beneficial for women. One association was found for dietary cholesterol being harmful for men. No plausible explanations were offered for either of these sex-based findings.

* The paper is asking us to believe that barely a gram or a couple difference in intake is associated with 27-37% differences in bladder cancer incidence. That’s relative risk. The absolute risk difference was tiny, and the claims were absurd anyway.

Introduction

We’re back to epidemiology this week, but it’s an interesting one. The paper is called “Dietary fats and their sources in association with the risk of bladder cancer: A pooled analysis of 11 prospective cohort studies” (Ref 1). The paper was published in January 2022, but it was recently reported by the UK Independent newspaper, which is when it came to my attention (Ref 2).

The paper opened with the global position on bladder cancer. It is the 10th most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide, with approximately 573,000 new cases and 213,000 deaths each year (Ref 3). Approximately 75% of bladder cancer cases are nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) “characterized by frequent recurrences, which requires intensive treatments and follow-up measures, posing a large burden on the national health care budgets and patient’s quality of life” (Ref 1).

The introduction to the paper noted that previous research has reported that fluids, fruit, vegetables and yogurt are associated with reduced risk of BC, while a ‘Western diet’ has been associated with a higher risk. This study set out to examine the effect of fat intake from different dietary sources on bladder cancer. It found and pooled data from 11 population studies. These included the countries involved in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC), which are Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and United Kingdom. Plus, the Netherlands cohort study and the North America VITamins and Lifestyle cohort study (VITAL).

The study

The study was a case control study. This means that a number of cases (2,731) were identified, and a number of non-cases (544,452) were used as comparators. There were 5,400,168 person-years of follow-up. The average (median) follow-up was 11.4 years.

The differences in characteristics of people who were cases and people who were non-cases need to be adjusted for so that the only difference left is the factor of interest – in this case dietary fat. That is virtually impossible to achieve.

Table 1 in the paper was the usual characteristics table. There was no column to confirm which measures were statistically significantly different, which was bad practice. There were some differences that were so visibly different, that they would have been significantly different. Some characteristics showed that the cases were completely different people to the non-cases. The cases had an average age of 60 vs 51 in the non-cases. They were male in three quarters of the cases. They were almost twice as likely to be current smokers and far more likely to have ever smoked. There was no information on other characteristics, which probably were different and should have been adjusted for e.g., activity levels, education, income. There was information on alcohol intake: beer intake was higher and wine intake was lower in the cases.

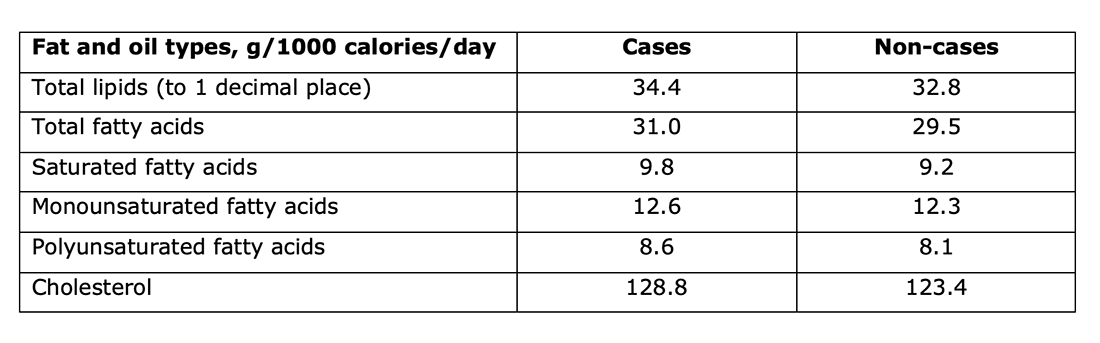

The dietary information in the characteristics table was striking. I’ve extracted the intake (in grams per 1,000 calories consumed each day) for the main categories that were reviewed – total lipids, total fatty acids, saturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids and dietary cholesterol. Section 3.1 of the paper reported that the differences between the intakes for cases and non-cases were statistically significant. The differences were not significant in the normal use of the word. The difference in total lipids was 1.65g, for example. Good luck even measuring that.

In the recent sweeteners and cancer paper we reviewed, the lowest artificial sweeteners intake (mg per day) was 0 and the highest intake group averaged 79 mg per day (Ref 4). The table in that paper reported those as significant differences, but it didn’t need to. Those are visible differences. This fats and bladder cancer was striking in the similarity between the fat intake of the cases group and the non-cases group.

The characteristics table tells us that the main risk factors for bladder cancer are sex, age and smoking. People can not smoke, but sex and age are not modifiable risk factors. This paper tried to adjust for those main risk factors to tell us that some fats are risk factors.

The results

The raw differences in fats were so small, that they were barley differentiable. However, the next stage of the study split the intake into tertiles – that’s three equal groups. Tertile 1 was the lowest intake and tertile 3 the highest. The paper noted that “The intake of some plant-based fat sources was not variable enough to be categorized into tertiles (ie, corn oil, soya bean oil, rapeseed oil, grapeseed oil, peanut oil and sunflower oil). For these sources we used the median intake as a cut-off to categorize the participants into low and high intake groups.” The paper did not report the intakes in each tertile, which was also bad practice. We don’t know, therefore, how similar the intake of fats was between the highest and lowest groups. (We can guess that it was very similar, because of the small differences in the cases vs non-cases top-level data).

The main findings were that, among women, when comparing the highest and lowest tertile intakes, an inverse association was found between intake of monounsaturated fat and BC risk. i.e., higher monounsaturated fat intake (think olive oil) was associated with lower incidence of bladder cancer. This was only observed for the nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) subtype. Among men, a higher intake of dietary cholesterol was associated with a higher BC risk. No other significant associations were found. Not one association held for both sexes.

Looking at the tables in the papers, the lack of findings was clear. In models adjusted for age, sex, smoking, energy intake, beer, wine and sugar intake, there were NO findings for the following:

– Total lipids and cases of bladder cancer;

– Total fatty acids and cases of bladder cancer;

– Saturated fatty acids and cases of bladder cancer;

– Polyunsaturated fatty acids and cases of bladder cancer.

There were findings for monounsaturated fats and BC (higher monounsaturated fat and lower BC), but only in women. There were findings for dietary cholesterol and BC (higher dietary cholesterol and higher BC), but only in men.

Only one dietary fat source was claimed to be associated with BC and that was animal fat. The animal fat intake for cases was 0.22g per 1,000 calories per day and for non-cases it was 0.16g per 1,000 calories per day. To one decimal place, those are both 0.2g/1,000 calories/day. Barely a discernible difference. Yet this was claimed (after adjustment) to account for almost a four fold difference in BC incidence. That is not credible.

The usual flaws

1) This is association, not causation.

2) Relative vs absolute risk. The relative risks were presented as follows (comparing the highest tertile intake with the lowest): Monounsaturated fats in women were associated with a 27% lower BC incidence; dietary cholesterol in men was associated with a 37% higher incidence of BC.

The overall incidence of BC was 2,731 cases in 5,400,168 person-years. That means approximately 1 case per 2,000 person years. If that were 1.2 cases per 2,000 person years, who cares? And that will be mainly driven by sex, age and smoking, remember.

3) The healthy person confounder. If smoking is a big risk factor and cases of bladder cancer drink more beer and less wine, there is a healthy person confounder going on. By not even reporting measures of affluence, let alone adjusting for them, this has not been addressed.

There are always the dietary questionnaire flaws underpinning the 11 studies pooled for this paper.

Taking stock

Essentially nothing has been found. No associations were found for incidence of bladder cancer and total lipids, total fatty acids, saturated fatty acids and/or polyunsaturated fatty acids. Associations were found for women only and monounsaturated fat and for men only and dietary cholesterol. This made the discussion section amusing, as the researchers tried to present possible mechanisms for monounsaturated fat being beneficial and dietary cholesterol being harmful. Yet if monounsaturated fat isn’t beneficial for men and dietary cholesterol isn’t harmful for women, what could a plausible mechanism be?

The discussion section resorted to hypothesising that the men/women monounsaturated fat discrepancy “might be related to overall gender differences in reporting diet… Women being more likely to report their diet as healthy”, i.e., lying. Ouch! Another explanation offered was that “the sex hormone profile in itself (especially androgens) might play a role in the development and progression of BC.” And it might well do. But that has nothing to do with dietary fats.

The cholesterol explanation was no better. The first statement was “it remains unclear why in the present study a discrepancy between men and women was observed.” The second hypothesis was that oestrogen might protect against certain diseases. And it might well do. But that has nothing to do with dietary fats. The final suggestion was interesting “increased use of statins among men compared to women need to be taken into account in future research on the gender specific relation between cholesterol and BC.” That shows ignorance in confusing dietary cholesterol with blood cholesterol. Men are more likely to take statins for blood cholesterol levels (albeit that women have higher blood cholesterol levels, on average, than men). This has nothing to do with dietary cholesterol. And statins might have an effect on bladder cancer, but that also has nothing to do with dietary fats.

Hence, we have virtually no results found and no plausible explanations for the two (sex-dependent) results that were found.

We don’t know what the intake of monounsaturated fat was in the lowest vs highest tertile for women. We do know that in all people the intake of monounsaturated fat in cases averaged 12.6g and the intake in non-cases averaged 12.3g per 1,000 calories We are being asked to believe that an approximate 0.3g difference in monounsaturated fat made a 27% difference in bladder cancer incidence. And without an explanation for this. That’s absurd.

We don’t know what the intake of dietary cholesterol was in the lowest vs highest tertile for men. We do know that in all people the intake of dietary cholesterol in cases averaged 128.75g and the intake in non-cases averaged 123.42g per 1,000 calories We are being asked to believe that an approximate 5.3g difference in dietary cholesterol made a 37% difference in bladder cancer incidence. And without an explanation for this. That’s absurd.

The main risks for bladder cancer are sex, age and smoking. Avoid smoking and that’s it, which is probably the key health advice for all cancer.

References

Ref 1: Dianatinasab et al. Dietary fats and their sources in association with the risk of bladder cancer: A pooled analysis of 11 prospective cohort studies. International Journal of Cancer. January 2022.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ijc.33970

Ref 2: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/health/world-cancer-research-fund-cholesterol-maastricht-university-b2127003.html?amp

Ref 3: Sung et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021.

Ref 4: https://www.zoeharcombe.com/2022/06/sweeteners-cancer/

https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1003950

0.06g difference? Really? Not enuf vomit emoticons….

A very useful piece of research, showing that fats are not apparently implicated in bladder cancer – why could they not just report this useful fact rather than clutching at straws to try to prove the opposite? It’s a shame that the public at large do not get the benefit of your analyses, my wife and I still struggle to get intelligent people to ignore the ‘fat is bad’ message which is still engrained in dietary ‘commonsense’.

Cheers,

Pete