Vasectomies: testing & clearance

Executive summary

* A paper has just been published in BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health about different testing strategies post vasectomy. I had the opportunity to be one of the authors.

* When a man has had a vasectomy, he and any affected partner want to know that it has worked. This requires a test. The desired outcome of the test is “clearance” i.e., clearance to abandon other methods of contraception and to trust that the vasectomy has worked.

* There are two main methods of submitting a sample for testing – postal and non-postal. The former involves getting a sample at home and posting it for testing and the latter involves donating a sample at a clinic.

* The paper was published under “original research”. It asked and answered important questions:

Q1) Does postal testing increase compliance?

Yes.

Q2) Following compliance how do clinical outcomes (early and late failures) compare?

Favourably.

Q3) What significance does this have for clinical practice?

More consideration should be given to supporting postal sample returns in procedural guidelines. When compliance is accounted for, postal strategy allows recommending cessation of other contraceptive methods (clearance) in one in five more men than a non-postal strategy.

* This paper could elicit procedural change in the vasectomy world.

Introduction

A friend in the village where I live, Dr Mel Atkinson, performs vasectomies. We got chatting about some data that she and a colleague were analysing, and I offered to help. Her colleague, Dr Gareth James, had amassed some valuable data on vasectomies performed in the UK from 2008 to 2019, as reported in annual audits by members of the Association of Surgeons in Primary Care (ASPC). Months later an article has just been published sharing the findings from the data (Ref 1). I found the whole subject area new and interesting, and I hope that you do too.

Vasectomies

Vasectomy is one of only two methods of contraception available to men, the other being the condom. It is available from the National Health Service (NHS) in most areas of the UK, carried out in hospitals, sexual and reproductive health (SRH) clinics and in primary care settings as well as by private providers. This makes it difficult to accurately quantify the number performed annually, but approximately 12,000 were performed in 2017/18 in England in hospital and within SRH services.

The third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3) 2010 showed a significant decline in the prevalence of vasectomy use for contraception, but since 2016 there has been a small but sustained increase. It remains a valid choice for couples requiring non-reversible contraception as it is safer, quicker, associated with less morbidity and more effective than female sterilisation. Vasectomy is generally carried out under local anaesthetic, employing a minimally invasive technique and cautery. The incidence of complications is low.

Vasectomies are not undertaken without consideration. They are performed when a man is sure that he doesn’t want any or more children. When vasectomies have been done, the man and his female partner, want to know when they are safe to stop other methods of contraception. This requires a test, which is called post-vasectomy semen analysis (PVSA). This is usually undertaken around 12-16 weeks. This can give ‘clearance’ for other contraceptive methods to be stopped.

In the UK, men who have had a vasectomy may use two strategies to submit their semen sample for PVSA. They may submit a fresh semen sample, produced either at the laboratory facility, or at home and delivered to the laboratory according to local protocol. Alternatively, men may use a postal strategy, whereby they produce a semen sample at home and send it through the post to a laboratory for analysis. The latter is referred to as postal PVSA throughout our paper.

Most UK and international guidelines recommend the first option, allowing assessment of sperm motility. However, the compliance of men when asked to provide a fresh sample for PVSA is generally poor, with only approximately two-thirds of men submitting one sample. Many factors can compromise compliance with local laboratory testing, including lack of suitable appointments, embarrassment producing specimens on site, time restrictions, expense of transport, and loss of earnings while attending the clinic. Covid-19 has introduced additional complications with in-person testing.

In 2016, the Association of Biomedical Andrologists (ABA), British Andrology Society (BAS) and British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) advised against the use of postal PVSA, claiming sperm degradation. However, the American Urological Association (AUA) and the most recent Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) guidelines considered that postal semen sample submission is acceptable to decrease the inconveniences associated with submitting a fresh semen sample and to potentially increase compliance.

The aforementioned organisations recommend that clearance be given if no sperm are seen in the postal semen sample. At first PVSA, approximately 80% of vasectomised men will show no sperm, with only a minority required to produce additional postal or fresh samples.

The study aim

To the best of their knowledge, Mel and Gareth realised that no study had yet examined the difference in compliance and efficacy with a postal strategy vs. non-postal strategy. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to evaluate if the strategies for post-vasectomy semen sample submission (postal or non-postal) are associated with a difference in compliance (to provide all required semen samples), and/or a difference in early and late failure detection rates.

Early failure has occurred if any motile sperm are observed in a fresh sample seven months post vasectomy. The patient is informed that the vasectomy has been deemed unsuccessful, meaning alternative contraception must continue or a second operation will be required. The approximate rate of early failure is 1 in 200 procedures (Association of Surgeons in Primary Care (ASPC) Audit).

Late failure has occurred if the patient has been informed that they had a negative PVSA and were sterile and were safe to abandon contraception irrespective of when this happened. Late failure is usually uncovered with a pregnancy, apparently fathered by a vasectomised man who was given clearance. The approximate rate of late failure is 1 in 2,000 procedures (Association of Surgeons in Primary Care (ASPC) Audit).

The male is seeking clearance (on behalf of himself and any partner affected) to abandon other contraception and rely on the vasectomy procedure. Early failure, as described above, is simply sperm seen on a microscope slide, but late failure is clearly more than an inconvenience as pregnancy ensues.

In all of this, compliance is important, and clearance is important. Regarding the former, some men might not bother to produce a sample and might assume everything is OK post operation. Regarding the latter, clearance is the desired outcome for the patient, but it needs to be accurate.

Our research team wanted to know:

Q1) Does postal testing increase compliance?

Q2) Following compliance how do clinical outcomes (early and late failures) compare?

Q3) What significance does this have for clinical practice?

Methods

Surgeons subscribed to a postal or non-postal semen sample submission strategy and to the use of one-test or two-test clearance guidance throughout each audit cycle. The chosen options were usually determined by the surgeon’s preference and local availability. However, the commissioners or local laboratory may have dictated these choices.

We first calculated the number of vasectomies performed by surgeons who provided eligible audit forms and compared the proportion of vasectomised men whose surgeons reported using a postal and a non-postal semen sample submission strategy. We then calculated the absolute differences between these two groups according to the following outcomes: compliance, early failure and late failure. Compliance to all testing needed to establish the success or failure of vasectomy was calculated by adding the number of vasectomies with clearance given and those with early failure.

Results

A total of 90 different surgeons (between 22 and 44 per year) provided audit data on 71,112 vasectomies during the 11-year study period. The number of vasectomies for which data were collected annually ranged from 2,406 in 2008 to 8,713 in 2018–2019. Data were missing for 12,212 vasectomies, which excluded them from our analysis. Among the 58,900 (83%) vasectomies eligible for analysis, the postal semen sample submission strategy was more commonly used (56%) than the fresh sample non-postal strategy (44%).

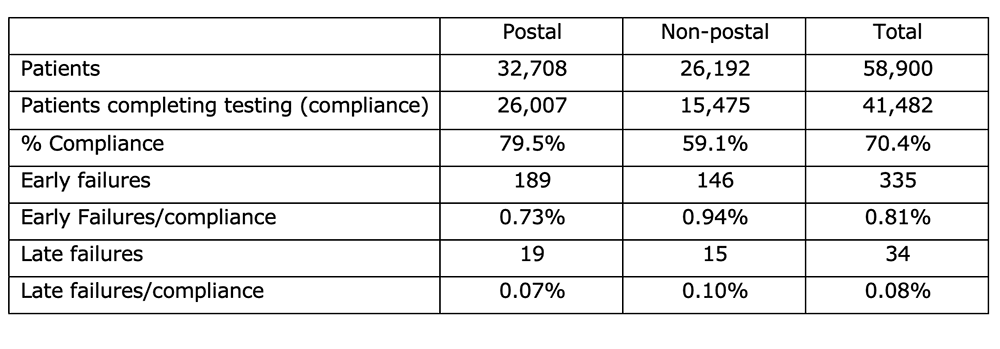

The table below collates the key numbers from Table 1 in the paper. Patients add up to 58,900 and this is the number of vasectomies for which we had complete data. Of these, 41,482 completed at least one sample and this gave an overall compliance percentage of 70.4%. There were 335 early failures and 34 late failures reported.

These data enabled us to answer our research questions:

Q1) Does postal testing increase compliance?

A1) Yes. 79.5% of patients returned at least one sample via the postal method vs. 59.1% of patients via a non-postal method. This was an absolute difference of 20.4% (The 95% confidence interval was 19.7% to 21.2%, so this was a significant result).

Q2) Following compliance how do clinical outcomes (early and late failures) compare?

A2) They compare favourably. Differences were small for either failure rate, but non-postal testing detected slightly more early failure rates and this was (statistically) significantly different. There was no significant difference in late failures between the two testing methods (postal vs. non-postal).

– 189 early failures were recorded among postal samples and 146 among non-postal samples. As a proportion of samples returned, this represented a 0.73% early failure rate for postal vs. 0.94% early failure rate for non-postal. (The 95% confidence interval was -0.41% to -0.04%, so this was a statistically significant result).

– 19 late failures were recorded among postal samples and 15 among non-postal samples. As a proportion of samples returned, this represented a 0.07% late failure rate for postal vs. 0.10% late failure rate for non-postal. (The 95% confidence interval was -0.09% to 0.03%, so this was not a statistically significant result).

Q3) What significance does this have for clinical practice?

A3) We summarised the findings with these key messages:

– Postal semen sample submission strategy after vasectomy results in better compliance and similar early failure and late failure rates compared with fresh sample non-postal strategy.

– When compliance is accounted for, postal strategy allows recommending cessation of other contraceptive methods (clearance) in one in five more men than a non-postal strategy.

– As compliance is so significantly higher for postal testing it allows detection of 1 more early failure from 500 vasectomies assuming a 1% early failure rate.

– Postal semen sample submission strategy for post-vasectomy semen analysis warrants inclusion in future guidelines as a reliable and convenient option.

Strengths & limitations

The main strengths of this study are its sample size and the fact that it spans over a decade. This has enabled us to analyse data spanning a major change of guidelines. Data collection continues through the ASPC and thus this analysis can be repeated and reviewed. This review enables surgeons to compare their data over time and against other surgeons. The data reported appear to be valid. The compliance rate of about 60% for non-postal strategy, and the early (about 1%) and late failure (about 0.1%) rates reported for both postal and non-postal strategies are in line with evidence-based guidelines in the UK and North America.

This study has some limitations. We assessed the confounding and modifying effects of two major factors: number of tests guidance and study period. However, many different surgeons submitted data over more than a decade. We cannot presume consistency between them for experience, technique, reminder systems, time schedule for testing, and clearance/failure criteria used. There may also be variation between the two strategies in the types of practices/patients – including socioeconomic status and access to local laboratory services. These factors could influence the differences observed between semen sample submission strategies for compliance and failures. The difference in early failure detected for the two strategies may be due to an actual difference in the early failure rate, i.e., more experienced surgeons tending to use a postal method and therefore there were fewer failures to detect. However, we do not believe this would change our conclusions considering the scale of the difference in compliance.

Notification and recording of late failures (contraceptive failures) are likely to be imprecise and underestimated. For instance, pregnancies may occur many years after vasectomy and the surgeon might never be informed. In addition, our data cannot confirm that the reported late failures from both strategies were indeed true late failures as proven by fresh PVSA or DNA testing. As the numbers of late failures are small, any misdiagnosis could greatly affect the figures. Nevertheless, the reported late failure rate in our study, approximately 0.1% (1 in 1,000), may be more valid than the 0.05% (1 in 2,000) usually quoted.

Conclusion

The postal strategy of post-vasectomy semen sample submission is not only a less resource-intensive approach but is clearly more acceptable to patients. The higher compliance of postal strategy confers overarching benefits to patients, their partners, and surgeons seeking confirmation of vasectomy success, without compromising efficacy to detect failures. These benefits are even more crucial in the current climate of Covid-19, when it is clearly preferable for men to post a semen sample than to attend a clinic.

Our study should reassure both surgeons and patients who presently use postal semen sample submission strategy. It may also inspire more surgeons, commissioners and laboratories to follow this approach. Future clinical practice guidelines should recommend submitting semen samples by post as a reliable option.

References

Ref 1: Atkinson et al. Comparison of postal and non-postal post-vasectomy semen sample submission strategies on compliance and failures: an 11-year analysis of the audit database of the Association of Surgeons in Primary Care of the UK. BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health. July 2021. https://srh.bmj.com/content/early/2021/07/28/bmjsrh-2021-201064.full

(Any other references are in this paper if you would like to know the source for a particular point).