Red meat: the evidence

In last week’s newsletter, I said that I would be covering a couple of stories that emanated from the European Society of Cardiology conference, which was held in Munich between August 25th and August 29th. This story is more ‘inspired’ by the conference, rather than an ‘unpack’ of a conference presentation.

Do you remember the PURE study from September 2017? (Ref 1) We woke up to the headlines “Low-fat diets could increase the risk of an early death: Major study challenges decades of advice as it reveals fat has a PROTECTIVE effect”? (Ref 2) My Monday newsletter noted that PURE had the usual limitations of epidemiological studies – association not causation and relative vs. absolute risk – but it had none of the howlers of ‘that (not) low carb study’ from August 2018 (Ref 3). Being a truly global study, it also had some fascinating insights into characteristics beyond diet of the regions being compared.

One of the lead researchers for the PURE study, Dr Andrew Mente, presented further findings at the Munich conference. These were reported globally with headlines such as “Cheese and red meat are back on the menu after study suggests eating twice as much as officials advise” (Ref 4). “Eating cheese and red meat is actually good for you” (Ref 5). Mente and colleagues had found that consuming three portions of dairy and approximately one and a half portions of unprocessed red meat daily was associated with 25% lower rates of early death and 22% fewer heart attacks. Three portions of dairy could equate to two slices of cheese, 200ml of whole milk and 200ml of full-fat yoghurt. The red meat amount would be approximately 120-130g (4.5oz) daily, which would be a small steak. The red meat intake, which the PURE researchers found to be optimal, is almost double what public health advisors recommend.

This inspired me to share with you some evidence that I systematically reviewed in preparation for a presentation for the Sustainable Food Trust in November 2016. I have checked that the evidence has not been updated since my review. I was asked by the Sustainable Food Trust to present “A defence of red meat” at two meetings on the same day – one in London and one in Bristol. You can see the Bristol presentation here (Ref 6).

What I did

Since 1980, when the first “Dietary Guidelines for Americans” were published, other national dietary guidelines have been influenced by those in the US. The most recent Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2015) were published at the start of 2016. For my presentation in November 2016, therefore, the US evidence base was the natural place to start.

I reviewed the Nutrition Evidence Library, which was used by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) for the 2015 revision (Refs 7, 8). The first interesting thing to note is that red meat was not documented as a category. Red meat appeared in a category called “animal protein.” The second interesting thing to note is that all data used for “animal protein” for the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans came from 2010 i.e. nothing had been updated since the 2010 guidelines. One of the reasons Nina Teicholz works tirelessly for the US Dietary Guidelines to be evidence based is so that the committee will only make recommendations based on the current evidence.

The evidence that was documented examined the relationship between the intake of animal protein products and seven conditions: 1) Cardiovascular disease; 2) Blood pressure; 3) Type 2 diabetes; 4) Body Weight; 5) Colorectal cancer; 6) Prostate cancer and 7) Breast cancer.

I have numbered these 1-7 below. I went through each condition as follows:

Step A) List all evidence reported for each condition.

Step B) Assess if any claim were made against red meat specifically, within the general animal protein category. If yes – go to Step C. If no – move on to the next condition.

Step C) If claims were made against red meat, then examine the definition of red meat precisely – going back to original papers where necessary.

Off we go!

1) What is the relationship between the intake of animal protein products and cardiovascular disease?

The conclusion statement was:

“Limited evidence from prospective cohort studies show inconsistent relationships between intake of animal protein products and cardiovascular disease (CVD), with somewhat more positive evidence for processed meats and coronary heart disease (CHD)” (My emphasis) (P12 Ref 8).

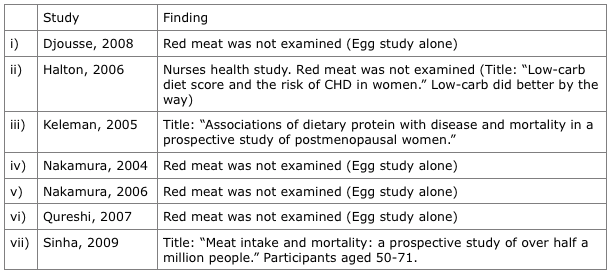

Evidence: The totality of the evidence for CVD comprised seven articles – four of which were entirely about eggs – which represented prospective cohorts from the US and Japan published since 2000 (full references for each study can be found in Ref 8):

Five studies (i, ii, iv, v, vi) can be ignored immediately in an examination of red meat: four were entirely about eggs (none found any association with eggs and CVD) and the Halton study did not examine red meat.

iii) Keleman’s key finding was: “Although no association was observed with any outcome when animal protein was substituted for carbohydrate, CHD mortality was associated with red meats (RR=1.44, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.94) and dairy products (RR=1.41, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.86) when substituted for servings per 1,000 kcal of carbohydrate foods.”

Keleman’s definition of red meat was: “A composite of beef, pork, and processed meat” (Ref 9). Keleman did not study red meat, therefore.

vii) Sinha’s conclusion was: “Red and processed meat intakes were associated with a modest increase in risk of total mortality, cancer and CVD mortality in both men and women. In contrast, high white meat intake was associated with a small decrease in total and cancer mortality.”

Sinha’s definition of red meat was: “Red meat included all types of beef and pork and included bacon, beef, cold cuts, ham, hamburger, hot dogs, liver, pork, sausage, steak and meats in foods such as pizza and chilli.” Sinha did not study red meat, therefore.

BOTTOM LINE: Not one study has even evaluated red meat, let alone found any evidence against it.

2) What is the relationship between the intake of animal protein products and blood pressure?

The conclusion statement was:

“Moderate evidence found no clear association between intake of animal protein products and blood pressure in prospective cohort studies.” (This conclusion was based on six studies: Alonso, 2006; Miura, 2004; Steffen, 2005; Wagemakers, 2009; Wang, 2008a; Wang, 2008b). (P36 Ref 8.)

BOTTOM LINE: Not even an association was found. There is nothing further to examine.

3) What is the relationship between the intake of animal protein products and type 2 diabetes?

The conclusion statement was:

“Limited inconsistent evidence from prospective cohort studies suggests that intake of animal protein products, mainly processed meat, may have a link to type 2 diabetes.” (My emphasis) (P59 Ref 8).

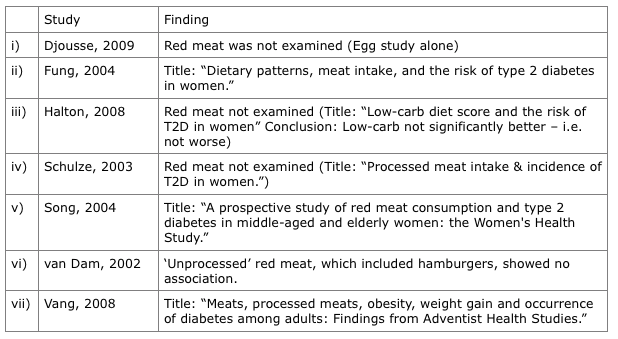

Evidence: The totality of the evidence for type 2 diabetes comprised seven articles – prospective cohorts from the US published since 2000:

Four studies (i, iii, iv, vi) can be ignored immediately in an examination of red meat: one was entirely about eggs; two did not examine red meat and Van Dam found no association with red meat (even with hamburgers included).

One of Fung or Song should also be ignored as they were papers using the same data source: the Nurses’ Health Study.

ii) Fung’s conclusion was: “Positive associations were also observed between type 2 diabetes and red meat and other processed meats.”

Fung did not define red meat alone and the conclusion included processed meat.

v) Song’s conclusion was: “Higher consumption of total red meat, especially various processed meats, may increase risk of developing type 2 diabetes in women.”

The red meat definition in Song was ”Red meat intake was considered to be the sum of hamburger, beef, or lamb as a main dish, pork as a main dish, beef, pork, or lamb as a sandwich or mixed dish, and all processed meat.”

It is extremely likely that the Song definition of red meat is the same as for Fung, given that both papers were about the Nurses’ Health Study.

vii) Vang’s conclusion was: “Meat intake, particularly processed meats, may be a dietary risk factor for diabetes.”

Red meat was not defined in Vang. Processed meat included salted fish!

BOTTOM LINE: Not one study has even evaluated red meat, let alone found any evidence against it.

4) What is the relationship between the intake of animal protein products and body weight?

The conclusion statement was:

“Insufficient evidence is available to link animal protein intake and body weight.” (This conclusion was based on three studies – Mahon, 2007; Wagemakers, 2009; Xu, 2007) (P83 Ref 8).

BOTTOM LINE: Nothing further to examine.

5) What is the relationship between the intake of animal protein products and colorectal cancer?

The conclusion statement was:

“Moderate evidence reports inconsistent positive associations between colorectal cancer and the intake of certain animal protein products, mainly red and processed meat.” (My emphasis) (P105 Ref 8).

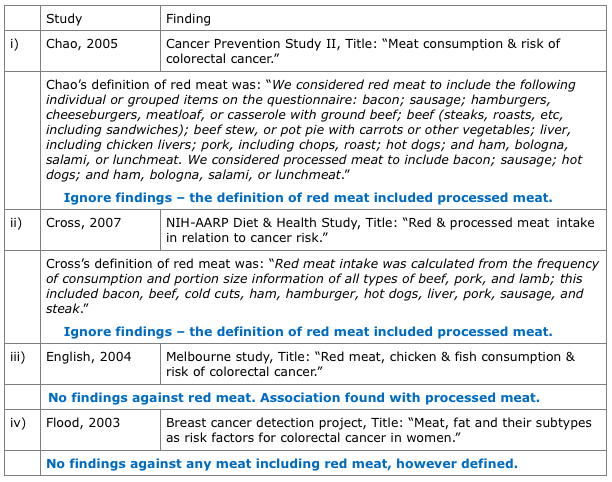

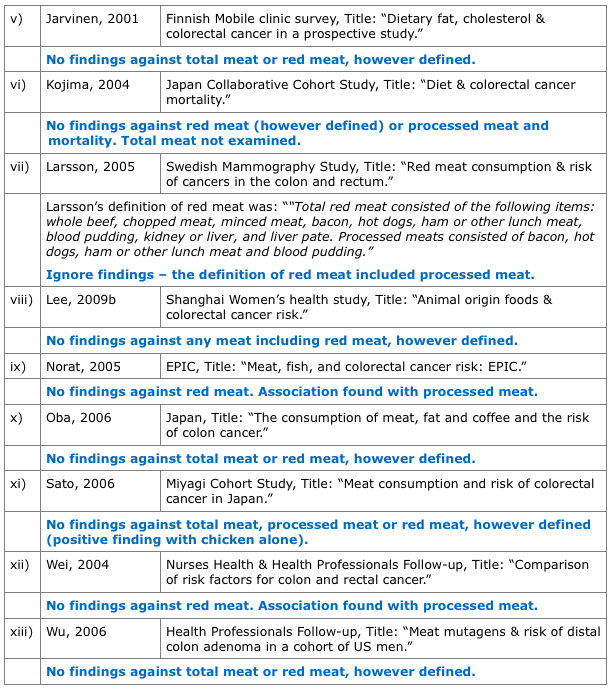

Evidence: The totality of the evidence for colorectal cancer comprised 13 studies (which represented prospective cohorts from the US, Europe, Australia, Finland, Japan, China and Sweden published since 2000).

The following are direct quotations from the evidence library: “In studies examining total meat intake, none reported a relationship with overall colorectal cancer risk (Flood, 2003; Jarvinen, 2001; Lee, 2009b; Oba, 2006; Sato, 2006) or risk associated with specific subsites (Lee, 2009b; Sato, 2006; Wu, 2006)… The EPIC study observed no association between red meat and colorectal cancer, but did observe a positive association for processed meat… Some studies found a relationship with rectal cancer and red meat intake [ZH – note – this was never actually red meat] (Chao, 2005; English, 2004), while others found no association (Kojima, 2004; Larsson, 2005; Lee, 2009b; Wei, 2004; Wu, 2006).”

“In general, the studies showed no consistent findings on type of meat or meat product and colorectal cancer” (P105 Ref 8).

BOTTOM LINE: There were no findings against red meat. I found the same when I examined this in April 2018 (Ref 10).

6) What is the relationship between the intake of animal protein products and prostate cancer?

The conclusion statement was:

“Limited evidence shows that animal protein products are associated with prostate cancer incidence” (P134 Ref 8).

Evidence: The totality of the evidence for prostate cancer comprised six articles (which represented prospective cohorts from the US published since 2000: Cross, 2005; Koutros, 2008; Michaud, 2001; Park, 2007; Rodriguez, 2006; Rohrmann, 2007).

Park, 2007 & Rodriguez, 2006 did not examine red meat. The other four studies found no association with red meat and prostate cancer.

The claim of limited evidence with animal protein products, not red meat, was due to findings in Michaud, 2001 (processed meat and metastatic prostate cancer) Rodriguez, 2006 (processed meat and prostate cancer in black, but not white, men) and Rohrmann, 2007 (processed meat and advanced prostate cancer).

BOTTOM LINE: There were no findings against red meat.

7) What is the relationship between the intake of animal protein products and breast cancer?

The conclusion statement was:

“Limited evidence from cohort studies shows there is no association between the intake of animal protein products and overall breast cancer risk.” (My emphasis) (P158 Ref 8).

BOTTOM LINE: There is nothing further to examine.

And that’s it. The totality of the evidence examined by the US Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, for the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, found nothing against red meat for 1) Cardiovascular disease; 2) Blood pressure; 3) Type 2 diabetes; 4) Body Weight; 5) Colorectal cancer; 6) Prostate cancer and 7) Breast cancer.

References

Ref 1: https://www.zoeharcombe.com/2017/09/the-pure-study/

Ref 2: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-4833096/Ditch-low-fat-diet-s-worse-health.html

Ref 3: https://www.zoeharcombe.com/2018/08/low-carb-diets-could-shorten-life-really/

Ref 4: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/08/28/cheese-red-meat-back-menu-study-suggests-eating-twice-much-officials/

Ref 5: https://nypost.com/2018/08/29/eating-cheese-and-red-meat-is-actually-good-for-you/

Ref 6: https://sustainablefoodtrust.org/articles/debating-the-role-of-livestock-with-joel-salatin/ (I’m on at 35 mins 54 seconds in)

Ref 7: The site was available here: https://www.cnpp.usda.gov/nutritionevidencelibrary/topic.cfm?cat=3138

Ref 8: The original site is being updated and all the data I reviewed can be found here https://www.cnpp.usda.gov/sites/default/files/usda_nutrition_evidence_flbrary/2015DGAC-SR-DietaryPatterns.pdf

Ref 9: Footnote to Table 7 (http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/content/161/3/239.full.pdf).

Ref 10: https://www.zoeharcombe.com/2018/04/red-meat-cancer/

Dr. Harcombe, I hope you are aware of a recent paper on this topic: Controversy on the correlation of red and processed meat consumption with colorectal cancer risk: an Asian perspective.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29999423

The abstract pointed out that most studies on meat and colorectal cancer risk have ignored 2/3 of humanity and “Among 73 epidemiological studies, approximately 76% were conducted in Western countries, whereas only 15% of studies were conducted in Asia. Furthermore, most studies conducted in Asia showed that processed meat consumption is not related to the onset of cancer. Moreover, there have been no reports showing significant correlation between various factors that directly or indirectly affect colorectal cancer incidence, including processed meat products types, raw meat types, or cooking methods.”

So if you include Asians there’s no correlation — until those Asians emigrate and change to Western diets.

Hi Craig – thanks so much for this – will tag it to look later – dealing with some other non-sense at the moment!

Best wishes – Zoe

Hi Zoe, first of all let me reveal I am woeful at anything I. T. So if my question is about something you have cleat answered on this site sorry. Have you posted any data for meat and dairy consumption over the past years and decades? Or if not here is it in one, or more, of your books? Thanks

Hi Sandy

I haven’t done anything on long terms trends on this site although I do monitor the UK Food intake in posts e.g.

https://www.zoeharcombe.com/2017/02/what-the-uk-eats-2014/

https://www.zoeharcombe.com/2014/03/what-the-uk-eats2012/

https://www.zoeharcombe.com/2013/11/what-the-uk-eats-2011/

My 2010 obesity book (here for subscribers https://www.zoeharcombe.com/the-obesity-epidemic/) has intake between 1974 to 2000 for the UK – the meat and dairy line items are meat down 40%, whole milk down 75%, butter down 76%

Try the Nutrition Coalition for US info https://www.nutritioncoalition.us/search?q=dairy

Good luck – Zoe

Thank you. Is such info more easily accessible from the USA?

Hi Zoe,

What do you think of tmao ?

Thank,

Gilles

TMAO is said to increase cardiovascular risk and meat / eggs are cited as high sources of TMAO. Several studies that showed a causal relationship between increased consumption of carnitine, choline and TMAO. However, some species of fish can increase serum TMAO much more than meat or eggs, yet fish are associated with a reduced cardiovascular disease risk. Moreover, only certain types of gut bacteria metabolise choline and carnitine to TMA, which is then converted by the liver to TMAO. Scientists have suggested that high TMAO levels may essentially be a result of an altered gut microbiome.

Most of the studies mention meat combined with grains and vegetables, such as pot pies, burgers, stews, lunch meat, hot dogs, meat puddings, and such. The most commonly eaten red meat is hamburger–how many people eat a burger without a bun, a soda, and a side of fries? I doubt they made any effort to separate the effects of the red meat alone.

Thanks for this article, Zoe! And thanks for making it available to everyone.

The testimonials from ex-vegans seem to be populating You Tube, and they are mostly unbelievable. The time frames seem to range from 1 to 20 years (Lierre Keith) until severe disease due to malnourishment occurs. The effects on children are especially tragic. Isn’t it way past time to start studying the health effects of an all-plant diet? In fact, why is meat consumption measured against plant consumption with the assumption that plants provide an optimal diet? If you look at the daily reported health tragedies due to veganism, even in children, perhaps it ought to be considered a public health concern.

The public health problem as it relates to nutrition has gotten so bad, a great many people are viewing it in terms of a conspiracy theory. sv3rge on You Tube is one such conspiracy theorist. He is doing a public service though in providing a platform for ex-vegans to tell their story. Here is one example of many, https://youtu.be/OAxQap0Rd0w.

My own view is that it is just another chapter in Charles Mackay’s book, written in the 19th century, “Extraordinay Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds.” Unfortunately it will take a number of generations to turn this around, if it gets turned around at all.

Hi Sburkeen

Many thanks for the youtube link – a friend’s daughter has just gone vegan – plus hubby and baby and she’s very concerned. I’ll send her the link.

Best wishes – Zoe

thank you for the comment, very interesting. and the link & reference to that book!

p.s. Z’s site here is killing me with all the math! hah. better than having to pick puzzle pieces out on an urban landscape! only hope it don’t go into long division …