Non-HDL cholesterol & cardiovascular disease

Executive summary

* This week we are reviewing a paper published in The Lancet, which was about non-HDL cholesterol and cardiovascular disease.

* The study used data from nearly 400,000 people from 38 different population areas and claimed that 1) there was an association between higher non-HDL cholesterol at baseline and the risk of cardiovascular disease events over subsequent years and 2) that this risk could be massively reduced if non-HDL cholesterol were halved.

* The paper was a risk-evaluation and risk-modelling study. Models are only as robust as their assumptions and this paper made many assumptions.

* To claim (1), among other assumptions, a few years of follow-up data were used to make estimates over decades.

* To claim (2), it was assumed that i) non-HDL cholesterol could be halved (with statins) and ii) that a mathematical formula could then be used to estimate hypothetical (their word) risk reduction as a result of taking statins for decades.

* An association between non-HDL cholesterol and cardiovascular disease is plausible, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that non-HDL cholesterol causes cardiovascular disease.

* The estimated reductions in cardiovascular disease were not plausible and they led to some quite absurd claims. These claims were the outputs of the model based on the researchers’ assumptions. It was claimed that risk could be reduced by up to 90% simply because they assumed it could be so.

Background

My first economics lecture at Cambridge University opened with the following joke: an economist, a marine biologist and a physicist are stranded in a boat with canned food and no can opener. They are discussing how they can get to the food to survive. The physicist suggests the angle of projection needed to throw a can at a sharp object in the hope that it will open. The marine biologist suggests dangling the can over the side of the boat to get fish to bite through the metal. The economist says, “let’s assume we’ve got a can opener.” At the end of three years of studying, we realised many a true word is spoken in jest. Economic modelling, as with modelling in any field, depends entirely on the assumptions.

Introduction

Every now and again I receive several emails about the same media story. That then tells me what the Monday note topic needs to be. That happened this week when a number of people sent me the latest cholesterol headlines “Heart experts demand checks for cholesterol from age of 25” (Ref 1). “Check your cholesterol from age 25” (Ref 2).

The paper behind these headlines was published in The Lancet on 3rd December 2019. It was called “Application of non-HDL cholesterol for population-based cardiovascular risk stratification: results from the Multinational Cardiovascular Risk Consortium” (Ref 3). Among the many authors, competing interests were declared with the following companies (many companies appearing several times): Abbott Australasia, Abbott Laboratories, Alphapharm, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Aventis Pharma, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Esperion, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Medtronic, Merck Lipha, Merck, Mylan, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pharmacia and Upjohn, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi Synthelabo, Sanofi, Servier, Servier Laboratories, Siemens, Singulex, The Medicines Company and ThermoFisher Scientific.

The goal of the study was to investigate “the relevance of blood lipid concentrations to long-term incidence of cardiovascular disease” (CVD). The first point to note is that this was a risk-evaluation and risk-modelling study. Economic modelling depends on the assumptions, so let’s look at what was done, what was found and what was assumed…

The study – what was done

The researchers used Multinational Cardiovascular Risk Consortium data from 19 countries across Europe, Australia, and North America. Individuals without CVD at baseline were included. The primary outcome of interest was a cardiovascular disease (CVD) event (Note 4). A CVD event was defined as the first non-fatal, or fatal, coronary heart disease or ischaemic stroke event. Coronary heart disease was defined as non-fatal or fatal heart attack including unstable angina, coronary death, and coronary revascularisation. The latter is very important. Revascularisation is the process of restoring flow to a blocked blood vessel. This is typically done by inserting a stent or a balloon. Such procedures are subject to human decision, whereas a heart attack (largely) isn’t. A cardiologist will recommend a revascularisation procedure if s/he detects compromised blood flow. It is more likely that the cardiologist will recommend such a procedure if the patient in front of them has an LDL-cholesterol of 5mmol/L (193 mg/dL) than, say, half that.

Non-HDL cholesterol was defined in the Lancet paper as total cholesterol minus HDL cholesterol. It was interesting to see this definition used, rather than the typical LDL-cholesterol. Non-HDL cholesterol includes VLDL (triglycerides), IDL (intermediate density lipoproteins), which rarely get mentioned and lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)), which Dr Malcolm Kendrick (among others) has long thought does have something to do with heart disease.

The researchers made a number of assumptions and then used the data and their assumptions in computer models. They cut the data for men and women separately and created various models adjusting for age, sex, cohort and “classical modifiable cardiovascular risk factors.” These were assumed to be smoking, diabetes, hypertension and obesity (sedentary behaviour was ignored). They then created a tool to estimate the probabilities of a CVD event by the age of 75 years, dependent on age, sex and risk factors and a modelled risk reduction “assuming a 50% reduction of non-HDL cholesterol.”

The study – what was found

398,846 individuals from 38 cohorts (a cohort is a population area e.g. Malmo, Sweden) were studied. The average (median) age was 51 years. At baseline, 40.1% of people were classified as having hypertension (defined as systolic blood pressure above 140 mmHg or taking antihypertensive medications); 4.8% had diagnosed diabetes and 33.3% were daily smokers. During an average (median) of 13.5 years follow-up, 54,542 CVD events occurred.

The second point to note is that this is an absolute average incident rate of 1% per year.

People were put into five groups depending on their baseline non-HDL cholesterol. The groups and the percentage of people in each group were as follows:

| UK measure (mmol/L) |

<2.6 |

2.6 to 3.7 |

3.7 to 4.8 |

4.8 to <5.7 |

≥ 5.7 |

| US measure (mg/dL) |

<100 |

100 to 145 |

145 to 185 |

185 to <220 |

≥ 220 |

| % of people |

5.1% |

26.2% |

33.3% |

20.4% |

15.1% |

Using data for baseline cholesterol and subsequent CVD events, using the lowest non-HDL cholesterol group as the reference (1.0), the hazard ratios for men and women were estimated to be as follows (see assumption in the next section):

| Group (mmol/L) |

<2.6 |

2.6 to 3.7 |

3.7 to 4.8 |

4.8 to <5.7 |

≥ 5.7 |

| Women |

1.0 |

1.1 (1.0-1.3) |

1.4 (1.2-1.6) |

1.6 (1.4-1.8) |

1.9 (1.6-2.2) |

| Men |

1.0 |

1.1 (1.0-1.3) |

1.4 (1.2-1.6) |

1.7 (1.5-2.0) |

2.3 (2.0-2.5) |

These estimates showed, the higher the baseline non-HDL cholesterol, the higher the risk of a CVD incident during the follow-up.

The study – what was assumed

The word assume (or derivatives thereof) appeared 14 times in the paper. The word estimate (or derivatives thereof) appeared 19 times in the paper. The following assumptions are worthy of note:

– In the table of hazard ratios above, available follow-up data were used for “individuals aged between 35 and 70 at baseline to estimate their probability of a cardiovascular disease event by the age of 75 years” (p4). With an average follow-up period of 13.5 years, some follow-up periods would have been longer than this and some just a few years long. Either way, they have been assumed to be applicable and extrapolatable to a hypothetical period of 40 years for a 35-year-old at baseline.

– 5% of individuals were receiving lipid lowering therapy at baseline (Table 2). “For individuals receiving lipid-lowering therapy, baseline concentrations of non-HDL cholesterol and LDL cholesterol were inflated by 30% for the analyses” (p3). That assumption would bump most people on statins at baseline up one or two cholesterol groups. Given that the researchers found that CVD event risk increased with baseline non-HDL cholesterol increases, this gives the perverse situation that being on statins increased one’s risk of an event in this model. (And yet the paper conclusion was that statins would massively reduce one’s risk of an event).

– Using the age of 75 and not 65 was an implicit assumption and the implications should be noted. The age of 65 is more typically used, because 65 has been seen as a reasonable age to describe a heart death/incident as “premature.” Using 75 takes us much closer to actual life expectancy and further away from “premature”, but it does increase the number of events and thus make potential risk reductions look bigger and better.

Most of the rest of the assumptions were related to the ‘tool’ developed to predict CVD risk. It was this tool that generated the media coverage with the UK Times reporting “a woman under 45 in the “medium” bad cholesterol category who had a number of other risk factors, such as diabetes, had a 16% chance of having a “cardiovascular event” by the age of 75. The researchers estimated how much this risk could be reduced if someone aged between 30 and 45 took steps to halve their level of bad cholesterol” (Ref 5).

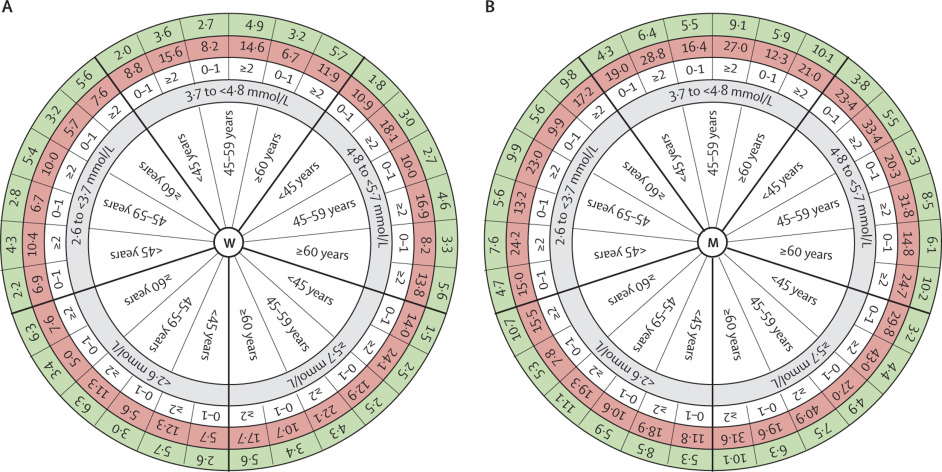

These words were based on Figure 4 (the coloured wheels) in the paper, which can be seen below.

The wheels are ‘busy’. The one on the left (W) is for women. The one on the right (M) is for men. The inner spoke of the wheel gives three age groups repeated for each of the five baseline non-HDL cholesterol groups (shown in grey). The white band beyond the grey band adds in the number of risk factors (for each age group – either 0-1 or ≥2). The red band gives the estimated risk of having a CVD event by the age of 75 years. The green band on the outside is described as: “The hypothetically achievable probability (%) for CVD by the age of 75 years after 50% reduction of non-HDL cholesterol” (my emphasis in bold).

The red band has been estimated from the data upon which this paper is based – the nearly 400,000 people from 38 different cohorts. The red band assumes that the average 13.5 years of follow-up can be extrapolated for up to 40 years (from the age of 35 to the age of 75).

The lowest risk estimate for any woman is 5%. This risk estimate is for a woman in the lowest baseline cholesterol group, aged 60 or over, with none or one risk factor. This woman is estimated to have a lower risk of an event than a woman under 45 with the same baseline cholesterol and 0-1 risk factors. There’s simply more time to have an event between 45 and 75 than 60 and 75!

The highest risk on either wheel is for a man (men have more CVD on average than women – although they have lower cholesterol on average too, remember) under the age of 45 in the highest cholesterol group and with 2 or more risk factors. Such a chap has an estimated 43% chance of a CVD event before the age of 75.

The green circle has been estimated to give the hypothetically achievable probability (%) for CVD by the age of 75 years after 50% reduction of non-HDL cholesterol. The green band is the one that has taken assumptions to a whole new level.

First this assumes that 50% reduction of non-HDL cholesterol is possible – right across the board, men and women, no matter what age, what risk factors, what base level of non-HDL cholesterol. Even if non-HDL cholesterol at baseline is below 2.6, it is assumed that this can be halved (Ref 6). Yet, only in April this year, we were told that statins don’t work for half the people that take them (Ref 7).

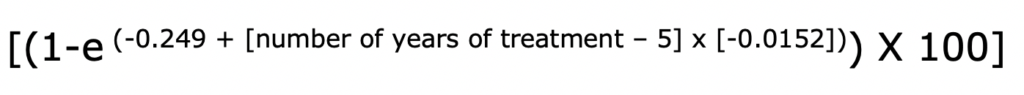

The second assumption is the big one. The paper has assumed that the hypothetical halving of non-HDL cholesterol delivers a formulaic reduction in CVD event risk. The precise formula used as an assumption for the computer modelling is reported on p4 of the Lancet paper:

(Where “e” is a mathematical constant that is the base of the natural logarithm: the unique number whose natural logarithm is equal to one. It is approximately equal to 2.71828.)

The reference for this was given as the Ference et al 2017 paper (Ref 8). The Ference et al paper describes this equation as “The expected proportional risk reduction per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C for any specific treatment duration.” The Lancet paper has assumed that this applies equally and precisely to non-HDL cholesterol.

All the numbers in the green band (and thus all the media claims) are based on this mathematical formula. There are only two variables in this mathematical formula i) by how many mmol/L can LDL-cholesterol (now assumed to be non-HDL cholesterol) be reduced? And ii) for how many years can statins be administered? (i) assumes that risk can be reduced more in people with higher baseline non-HDL cholesterol simply because the higher the cholesterol, the higher half of it is and (ii) assumes that risk can be reduced more in younger people simply because the younger the person, the longer they can take statins.

Based on these assumptions, the formula produces some absurd results:

– It is assumed that the highest risk woman (under the age of 45, with 2 or more risk factors, in the highest cholesterol group) can reduce her estimated risk of having a CVD event before the age of 75 from 24.1% to 2.5%. Taking statins is assumed to halve her non-HDL cholesterol (notwithstanding that she may be one of the one in two people for whom they don’t work) and it is further assumed to reduce her risk of having an event to just 2.5% over the next 30+ years. This woman is still likely an obese, diabetic, smoker with hypertension (at least two of those).

Remember the lowest risk woman in the red band? She still had a risk estimate of 5%. This model assumes that the highest risk woman of all will end up with half that lowest starting risk, just by taking statins.

– The same happens with men (of course – it’s a formula). The highest risk man (under the age of 45, with 2 or more risk factors, in the highest cholesterol group) is assumed to be able to reduce his risk of having a CVD event before the age of 75 from 43% to 4.4%. This also ends up at almost half the starting risk for the lowest risk man.

Even in the wildest of claims made in pharma-conflicted papers, I have not seen claims such as these. I simply do not accept that statins, even if they could halve cholesterol, and even if this were a maker of health (rather than a marker of health) can negate the risk factors of at least two of obesity, diabetes, smoking and hypertension (also a marker) in this way. I find such claims literally unbelievable. You can make up your own mind.

Making some sense of this

Let’s take a step back and look as simply as possible at what this paper has done.

1) First it has used a lot of actual population data to claim that there is an association between higher non-HDL cholesterol at baseline and the risk of subsequent CVD events. This shouldn’t surprise us for a number of reasons:

i) non-HDL cholesterol includes things that probably do matter – triglycerides (an indicator of carbohydrate intake) (Ref 9) and LP(a);

ii) revascularisation events, being subject to human judgement, are likely to be higher with higher non-HDL cholesterol;

iii) since low density lipoproteins carry substances that repair (cholesterol, protein, triglycerides, phospholipids), the body should have higher LDL when more repair is required. This positions LDL (and anything in it) as a marker of health and not a maker of health. It would thus make sense that higher non-HDL cholesterol at baseline would be associated with more events over the coming years.

2) Second this paper has then made a number of assumptions about halving non-HDL cholesterol and even wilder assumptions about the reduction in CVD event risk that this could achieve. It is this second part that grabbed the media attention.

The abstract of the paper concluded: “A 50% reduction of non-HDL cholesterol concentrations was associated with reduced risk of a cardiovascular disease event by the age of 75 years, and this risk reduction was greater the earlier cholesterol concentrations were reduced.”

No and no. The researchers assumed that a 50% reduction in non-HDL cholesterol could and would be achieved. The researchers assumed that a mathematical formula for risk reduction could be applied to that assumed 50% reduction in non-HDL cholesterol. The researchers’ assumed formula included the variable “number of years of treatment” and hence the formula produced a higher number, the earlier treatment started. The assumptions made it so.

The final paragraph of the paper stated: “However, since clinical trials investigating the benefit of lipid-lowering therapy in individuals younger than 45 years during a followup of 30 years are not available, our study provides unique insights into the benefits of a potential early intervention in primary prevention.”

No it doesn’t. Your study is the modelling equivalent of “let’s assume we’ve got a can opener”!

References

Ref 1: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/heart-experts-demand-checks-for-cholesterol-from-age-of-25-3rf8pv6qn?shareToken=585116e86600371de3beb0a11d37b480

Ref 2: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-50648325

Ref 3: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)32519-X/fulltext

Note 4: Many thanks to a colleague of Dr David Diamond for this observation and to David for sharing it with me – the paper only focused on CVD. “Persons with low cholesterol levels could be more prone to die from non-CVD causes, and thus be removed from the ‘pool’ of possible later deaths [and incidents] due to CVD causes.”

Ref 5: The Times (above) and this was the example given on p7 of the paper above Figure 4.

Ref 6: “We modelled the potentially achievable long-term cardiovascular disease risk, assuming a 50% reduction of non-HDL cholesterol” (p8)

Ref 7: https://www.zoeharcombe.com/2019/04/statins-dont-work-well-for-half-those-who-take-them/

Ref 8: Ference et al. “Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel.” European Heart Journal (2017). (The equation can be found in Table 2 on page 10).

Ref 9: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11584104

Did by any chance you reviewed another study that shared some of the same authors in 2017 from the European Heart Journal:

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/38/32/2459/3745109

Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel

A PB foods doctor shared a suspicious looking graphic claiming this was the source and that it established a linear dose response between CVD and LDL levels. Anyway looking for analyses to figure out just how much of a misrepresentation it is. Cheers!

Hi Paul

No I didn’t – but the Ference paper has become so highly cited, I’ll put it on the look at list!

Many thanks

Best wishes – Zoe

“An association between non-HDL cholesterol and cardiovascular disease is plausible”.

An association between bad smells and typhoid is plausible from a priori observation, but scientists worked out a long time ago that only one of the microorganisms causing bad smells caused typhoid and it could kill you just as quickly without being associated with any smell.

This is even worse, because scientists have worked backward to say “the smells are easy to detect, so we want you to forget about microorganisms, because we only have deodorants for sale”

What the non-HDL regression does is to predict risk without explanation. The same lipid tests, taken fasted and broken into HDL, TG and calculated LDL are informative about much more than just which statin to take. For example we know that, at a normal HDL level, someone with very high TG and low LDL is at much more risk than someone with moderately high LDL and low TG. We even know exactly what to do for the person with very high TG. Yet these two people will have exactly the same non-HDL cholesterol level.

They must think we’re stupid.

Oh wait, The Lancet published it, they do.

A cohort, in my opinion, is a group of people enlisted at the same time for the same reason – like a draft in the Army or class of ’19 in a school.

This is much what the Cambridge dictionary says

“a group of people who share a characteristic, usually age”

Location could be a distinguisher – the PURE Study must have cohorts from different places, but to me time is the primary thing; 19th century Swedes are in a different cohort from those in Malmo today.

Hi George

Many thanks for this – brilliant as ever!

Best wishes – Zoe

I have often wondered if the changes considered for blood serum lipid concentration are even relevant for whatever effect you are chasing. I think I estimated the particle number for LDL-p for my blood serum quantity and it was order 10^18. Decibels are used in acoustics because of the extreme range of the human ear relative to perception. I think it is order 10^12, the high end at which damage occurs. I once heard a lipidologist brag that he had lowered the LDL-c down to 30 mg/dl and noted no ill effects in his patient. The particle number will still be order 10^18. Whatever depends on that LDL particle number probably still sees saturation, and you can get away with it. You can also get away with a hell of a lot of mischief, and this study probably accomplishes that. Would you think that cutting the acoustic power in half would save your hearing if you had already reached the limit at order 10^12?

Ye Gods they are now desparately plumming the depths to try and prove that they are right about the lipid-heart hypothesis. Give up guys – the hypothesis is so 20th century bunkum – we’ve moved on.

I read this in the news a week or so back and my thought was “so what?”.

Given that CVS is an inflammatory disease/metabolic disorder and the chronic healing process for any inflammatory disorder requires cholesterol (and TGs rise in cardiometabolic disorders), what is so surprising about the non-HDL levels given that these are markers, and not causes, of metabolic disorder.

The first question on seeing raised non-HDL levels in an individual should be: where’s the inflammation. The second question: how do we manage it?

I was interested to see, for instance that 33% of the study opulation were smokers – that would be a good start for managing inflammation. As a clinician it has never ceased to amaze me how soon TC and LDL levels in individuals reduce significantly after smoking cessation.

Also interested to know what the chronic stress levels were amongst this population. Any cohorts from eastern european countries would definitely have skewed the results with their stress levels in the last 30 years.

Good point! Dr Uffe Ravnskov said the same when he saw the paper:

“This paper, as many others, has the usual bias. Studies of both total cholesterol and non-HDL as risk factors mainly include young and middle-age people, and young and middle-age people are most likely more stressed than retired citizens. As stress is able to raise cholesterol by up to 50%, a relevant question is of course whether the higher risk of CVD among people with high lipid levels is caused by their high non-HDL cholesterol or by stress, because stress may increase the risk by other mechanisms than by raising cholesterol. That stress may be more important is supported by the finding that the risk (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6758015)”

Best wishes – Zoe

“An association between non-HDL cholesterol and cardiovascular disease is plausible, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that non-HDL cholesterol causes cardiovascular disease.”

An association between firemen (sorry fire person) and fires is plausible, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that firemen cause fires (just because the are nearly always found at the scene of the fire) .