Statins in the over 75s

Executive Summary

* Headlines in July 2020 reported that “A study of over-75s found that those taking statins were 25 per cent less likely to die from any cause.”

* The headlines came from a study published in JAMA, which reviewed data from 326,981 veterans (average age 81, mostly male, mostly white) who presented at a health clinic, some of whom started taking statins during a 6-7 year follow-up period.

* The study claimed that there were 79 deaths from any cause per 1,000 person years among statin users and 98 deaths from any cause per 1,000 person years among non-statin users. That’s where the 25% (relative) difference came from.

* The raw data in the paper showed that there were 93 deaths from any cause per 1,000 person years among statin users and 77 deaths from any cause per 1,000 person years among non-statin users. Almost the exact opposite of the headline claim.

* The entire claim rests on the statistical technique used for adjustment. There were differences between the people who went on to take statins and all the participants in the study. We are being asked to believe that adjustment for these differences flipped the finding from ‘more statin users died’ to ‘fewer statin users died’.

* This study was one observational study. There is higher level evidence available. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials was published in February 2019. It claimed that 8,000 deaths per year could be avoided in the UK if statins were taken by all people over the age of 75. I found that this was false. It relied upon evidence in the over 75s for both deaths and primary prevention (people who do not already have heart disease) and neither was found.

* This falsehood was also picked up by Nigel Hawkes who undertook an investigation for the BMJ. Hawkes reported “It [the meta-analysis paper] showed that over 75s who took statins and had no history of heart problems were no more likely to survive over the next five years than people not taking them.”

* The potential financial gain from putting all elderly people on statins is vast. The claims of benefit do not withstand scrutiny.

Introduction

A friend sent me a link to an article in The Times on July 8th, 2020. The headline said, “Daily statin can add years to elderly lives” (Ref 1). The opening paragraphs of the article reported: “Taking statins every day can add years to elderly people’s lives, according to research. A study of over-75s found that those taking statins were 25 per cent less likely to die from any cause. The pills lowered the risk of having a stroke or heart attack by a fifth. The findings, which applied even to people in their nineties, add to a growing body of evidence that thousands of deaths could be prevented every year if more elderly people were prescribed statins.”

Wow! That would have even me on statins in my elderly years, except that I’ve looked at this topic before – in February 2019 – and the data didn’t withstand scrutiny (Ref 2). Let’s have a look at where this latest headline came from, where it fits in the hierarchy of evidence and whether the claims really are as impressive as they seem.

The study

The newspaper headlines (The Times was not alone in covering this) emanated from a paper published in JAMA called “Association of statin use with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in US veterans 75 years and older” by Orkaby et al (Ref 3). The study was a retrospective cohort study which means that the researchers didn’t do a trial – they looked back at existing data to spot patterns.

In this case, the data came from 326,981 veterans, who made a visit to the Veterans Health Administration clinic between 2002-2012, and were then followed-up for an average (mean) of 6.8 years. The veterans had an average (mean) age of 81; 97% of them were men and 91% of them were white. This is not a group that is generally reflective of the entire US population, let alone a wider global population and is, therefore, not generalisable. The participants included in the study were free from heart disease and not taking statins at the study baseline.

During the follow-up, 57,178 of the 326,981 people started taking statins. The study should have been a comparison of the outcome for the 57,178 people who started taking statins vs the 269,803 who didn’t start taking statins and in parts it was. But in the important analyses, the study compared the 57,178 people who started taking statins with the 326,981 people in the entire study. The rationale was that everyone started as a non-statin user and everyone contributed some time to the non-statin user group, therefore. But those who went on to take statins were counted in both groups for characteristics and in both groups for the analysis that led to the headline claims.

The study reported that, during the 6.8 years of follow-up, there were 206,902 deaths from any cause and 53,296 deaths from cardiovascular disease.

The results were presented as:

– There were 78.7 all-cause deaths per 1,000 person years among statin users and 98.2 all-cause deaths per 1,000 person years among non-statin users. That’s where the 25% difference comes from – (98.2-78.7)/78.7 = 25%. That’s the relative risk difference, which is what is presented to make numbers look impressive. The absolute risk difference is 98.2 minus 78.7 = 19.5 in 1,000 = 1.95%, which is rather less impressive.

– There were 22.6 cardiovascular deaths per 1,000 person years among statin users and 25.7 cardiovascular deaths per 1,000 person years among non-statin users. That’s a relative risk difference of 14% and an absolute risk difference of 0.3%.

However, even the relative risk difference numbers did not withstand scrutiny. Before we take a look at these, let’s capture some other interesting findings in the study:

Interesting aspects of the study

* 63% of all people in the study died. That’s not hugely surprising given that the average starting age was 81 and 97% were male and they were followed for an average of 6.8 years. Had everyone lived, the average age at the end of the study would have been between 87 and 88 years old. However, this is still a high study death rate and it gives researchers a lot of deaths to consider.

* The opening sentences were interesting: “adults 75 years and older are the fastest-growing segment of the population. By 2050 more than 45 million Americans will be 75 years and older, with a proportional rate of increase greatest in those 85 years and older.” That tells us that making a case for statins in the over 75s would be very lucrative.

* There were 7,242,193 people in the starting pool to be considered for this study. These were veterans seen at the Veterans Health Administration clinic between 2002 and 2016. Of these, only 648,677 had no previous statin prescription. That’s below 9% of potential participants. The 648,677 was then further reduced for 179,428 people who had had a previous atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) event. Those with missing demographic data were also excluded. The final 326,981 people used for the study came from a large pool, but it was the fact that over 91% had been on statins previously that grabbed my attention. This also adds to the generalisability issue as this study is now only applicable to veterans, mostly male and white, with an average age of 81, who have never taken a statin or had a previous ASCVD event.

* People with other conditions – cancer, dementia, high blood pressure, diabetes etc – were not excluded from the study “to create a cohort of adults that reflects usual clinical practice.”

* The paper reported “Those who died within 150 days of entry into the cohort were excluded to avoid selection bias, as statins for primary prevention are estimated to take 2 to 5 years for benefit and are generally not recommended for those with very limited life expectancy.” That statement potentially undermines the entire case for statins in the elderly, as all men (and women) with an average age of 81 have limited life expectancy. Also, if statins for primary prevention are estimated to take 2 to 5 years for benefit, and people were followed-up for 6.8 years, unless people started taking statins very soon after the start of the study, there wasn’t much time for statins to help.

* The outcome part of the paper reported “If an event was observed on the same day as a new statin prescription, this was counted as an event in the statin nonuse group.” Someone is most likely to be prescribed statins when they’ve arrived at a medical clinic having a heart attack. This alone makes it highly likely that heart incidents will be attributed to the non-statin group.

The participants

As I often say, the characteristics table is the treasure trove. Typically, the characteristics table would have the people who didn’t go on statins in one column and the people who did go on statins in the next column and then we would see how they differed for baseline characteristics from age to BMI to smoking to diabetes etc. This paper reported all the 326,981 people in one column and the subset of this – the 57,178 people who went on a statin – in the next column. That means that the data for the subset are reported in both columns and it reduces the distinction between the two columns. The rationale for this was given as “all participants entered [the study] as non-statin users.” Yes, but the comparison we’re doing is between those who stayed nonusers and those who went on to take statins.

There were marked differences in some characteristics. In their favour, the statin users were more likely to have never smoked, they were less likely to have dementia and less likely to have liver disease. More things worked against the statin group, however. Statin users were twice as likely to have diabetes, and more likely to have hypertension, cancer, arthritis, and congestive heart failure. 64% of those who ended up on statins were taking more than 5 drugs at baseline vs 39% of those who didn’t end up on statins (Note 4 – the compliant patient confounder). Those who went on to take statins had almost 3.5 times the incidence of hyperlipidemia (defined as ICD 9 Codes 272.4; I don’t know what cholesterol number this equated to). I expect that this was seen as a disadvantage for the statin group and adjusted for as a disadvantage. However, many papers, since 1989, have reported lower mortality with higher cholesterol (read that carefully) in elderly people and thus this alone could have given the patients with higher cholesterol a health advantage (Ref 5).

These differences were not adjusted for in the usual way (regression analysis). This study used a statistical technique called “Propensity score overlap weighting”. (Watch this space – this is going to become far more commonly used). This attempts to ‘iron out’ the differences between the two groups as if they had been randomised to a group – in this case the statin group vs the no-statin group. We’ll come back to this.

The raw numbers

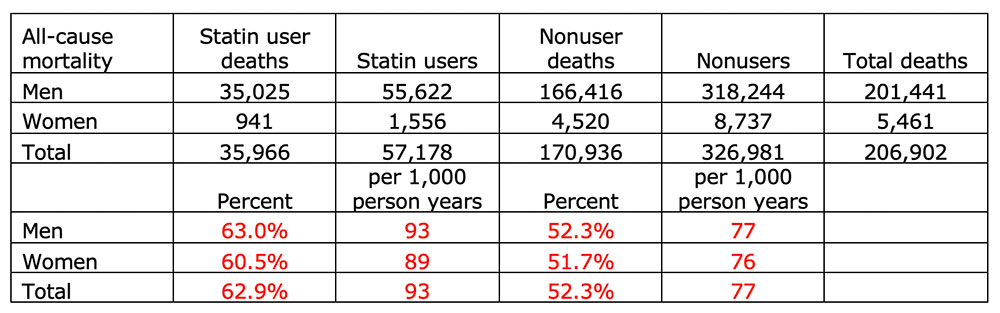

Figure 1 made me doubt the robustness of the process. Figure 1 looked at all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality for statin users and non-statin users broken down into subcategories. In the table below, I’ve extracted the data for all-cause mortality for men and women and then I’ve done some calculations. The figures extracted are in black and my calculations are in red:

We can observe the following from the above table:

– The number of statin users adds up to 57,178, which is what we have been told.

– The number of non-statin users adds up to 326,981, which is not non-statin users – it is everyone observed in the study. People who went on to be prescribed a statin are thus being compared with everyone who was recruited to the study, albeit only using the ‘nonuser’ period of time for those who went on to take statins.

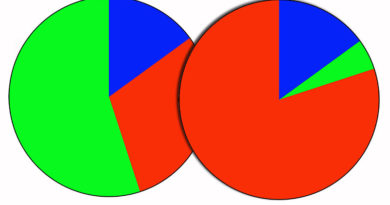

– Simply taking deaths/users, 63% of men statin users died vs 52.3% of men nonusers and 60.5% of women statin users died vs 51.7% of women nonusers. Substantially more statin users died, therefore. Yet, Figure 1 presented these data as a 25% lower risk for men and a 22% lower risk for women taking statins!

– A crude person-year calculation showed that there were 93 statin deaths per 1,000 person years and 77 non-statin deaths per 1,000 person years. Almost the exact opposite of the headline claim.

Everything comes down to the adjustment, therefore. The goal of the propensity score overlap weighting statistical technique is to adjust in an observational study as if the two groups had been randomised. The characteristics table tells us that the statin subset were more likely to have never smoked and less likely to have dementia, but twice as likely to have diabetes and more likely to have hypertension and cancer. So, swings and roundabouts, but there were some big roundabouts.

The raw data tell us that 63% of statin users died and 52% of nonusers died. That’s 93 per 1,000 person years vs 77 per 1,000 person years. Then the statistical technique was undertaken, and the results flipped over such that 98 per 1,000 person years of nonusers died vs only 79 of statin users. We have no way of challenging that and we’re just expected to believe it.

I sent a number of questions to the authors and they replied promptly. One of my questions was:

Q) “If we just take the men and women numbers in Figure 1, 63% of men statin users died vs 52.3% of men statin nonusers. Similarly, 60.5% of women statin users died vs 51.7% of women statin nonusers. How did this end up as favours statins?”

The answer was:

A) “The raw, unadjusted and unweighted number of events are shown in the figures. After adjustment, we found a lower risk of mortality in those who were newly prescribed a statin.”

I’ve told you what happened; you can decide if you believe it or not.

The hierarchy of evidence

Evidence from an observational study is inferior to evidence from a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) and a meta-analysis of RCTs provides even higher evidence. A meta-analysis of RCTs on exactly this topic was published in The Lancet on February 1st, 2019 by the Oxford CTSU. It was reported worldwide as “giving statins to people over the age of 75 could save thousands of lives.” The claim came from a press conference to launch the Lancet Paper, where a lead author, Colin Baigent, was quoted as saying: “Only a third of the 5.5 million over 75s in the UK take statins and up to 8000 deaths per year could be prevented if all took them.”

This is false. It relies upon evidence in the over 75s for both deaths and primary prevention (people who do not already have heart disease) and neither was found. Figure 5 in The Lancet paper confirmed that the Rate Ratio (RR) for vascular deaths for over 75s was not statistically significant. Nor was it for those aged 70-75 for that matter. Even with the attempt to achieve a significant result, by excluding trials that failed to show benefit of statins, the RR for vascular deaths for over 75s was not statistically significant. Figure 4 in The Lancet paper confirmed that the RR for major vascular events for over 75s without vascular disease was not statistically significant. Nor was it for those aged 70-75 for that matter.

This falsehood was also picked up by Nigel Hawkes who undertook an investigation for the BMJ (Ref 6). He also found that the two results [that I found] were not statistically significant. Hawkes reported “It showed that over 75s who took statins and had no history of heart problems were no more likely to survive over the next five years than people not taking them” (my emphasis in bold).

Hawkes, as part of his BMJ article, was able to interview Colin Baigent and ask him how he justified his statement. As Hawkes’ article reported, Baigent defended the conclusions as follows: “Instead of asking whether it works in this age group [over 75s], it is more appropriate to ask whether there is a reasonable level of proof that it does not work. In other words, can we really be sure, before we deny statins to a large population at increased risk, that statins will not work in this age group?”

If the CTSU cannot provide evidence that statins work for over 75s, you can be sure that there is no evidence. If there were, they would have published it. We now live in a world where a research team can find no proof but is allowed to ask instead – but what if there were proof?

References

Ref 1: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/daily-statin-may-add-years-to-elderly-lives-xdfffgqqw#

Ref 2: https://www.zoeharcombe.com/2019/02/statins-in-the-over-75s/

Ref 3: Orkaby et al. Association of statin use with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in US veterans 75 years and older. JAMA 2020. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2767861?

Note 4 – this introduces the healthy person confounder. It is known that people who take meds also seek medical attention more often and are more likely to follow the advice that they are given. This means that they tend to follow diet, exercise and smoking advice as well as medication advice. This was confirmed in the characteristics table by the fact that people who went on to take statins – and who were far more likely to be taking more than five drugs at baseline – were far less likely to smoke.

Ref 5: Forette et al. Cholesterol as a risk factor for mortality in elderly women. The Lancet. 1989. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140673689928651

Krumholz et al. Lack of Association Between Cholesterol and Coronary Heart Disease Mortality and Morbidity and All-Cause Mortality in Persons Older Than 70 Years. JAMA. 1994. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/381733

Irwin et al. Cholesterol and all-cause mortality in elderly people from the Honolulu Heart Program: a cohort study. The Lancet. 2001. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140673601055532

Hamazaki et al. Cholesterol Issues in Japan – Why Are the Goals of Cholesterol Levels Set So Low? Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2013. https://www.karger.com/Article/Fulltext/342765

Ravnskov et al. Lack of an association or an inverse association between low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality in the elderly: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/6/6/e010401.full.pdf

Ref 6: Hawkes. Could giving statins to over 75s really save 8000 lives a year? BMJ. 2019. https://www.bmj.com/content/365/bmj.l1779

So despite more dying in the intervention group, and before any side effects are mentioned, and before any cost is discussed, they still conclude that it’s worth it? What do we have to do when the pro statin lobby come out with a paper of their own that shows harm and they still publish it?

But what about people who have had a heart event?. That is constantly stated as being the overriding factor in favour of statins.

Great work, Zoe. Awesome review and critique. Thank you very much.

This seems to be a criminal misuse of statistical “correction” of data. This type of manipulation is very annoying, as they seem to be able to selectively choose a hierarchy of co-morbidities to get the outcome they want and nobody can check the analysis.

Were there any conflicts of interest that might explain their motivation?

Richard

Hi Richard

“Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Djousse reported receiving grants from Merck. No other disclosures were reported.

Funding/Support: This research was supported by VA CSR&D CDA-2 award IK2-CX001800 (Dr Orkaby), National Institute on Aging R03-AG060169 (Dr Orkaby), and VA Merit Award I01 CX001025 (Dr Wilson and Dr Cho).

I wouldn’t be surprised if there were some indirect funding going on – veterans or national institute for aging getting something and thus just the direct funding is declared. That’s been the thing for quite a few years now.

Best wishes – Zoe

Baigent LOGIC of:

“Instead of asking whether it works in this age group [over 75s], it is more appropriate to ask whether there is a reasonable level of proof that it does not work. In other words, can we really be sure, before we deny statins to a large population at increased risk, that statins will not work in this age group?”

Is the same kind of “LOGIC” that mandates the wearing of dehumanising face muzzles.